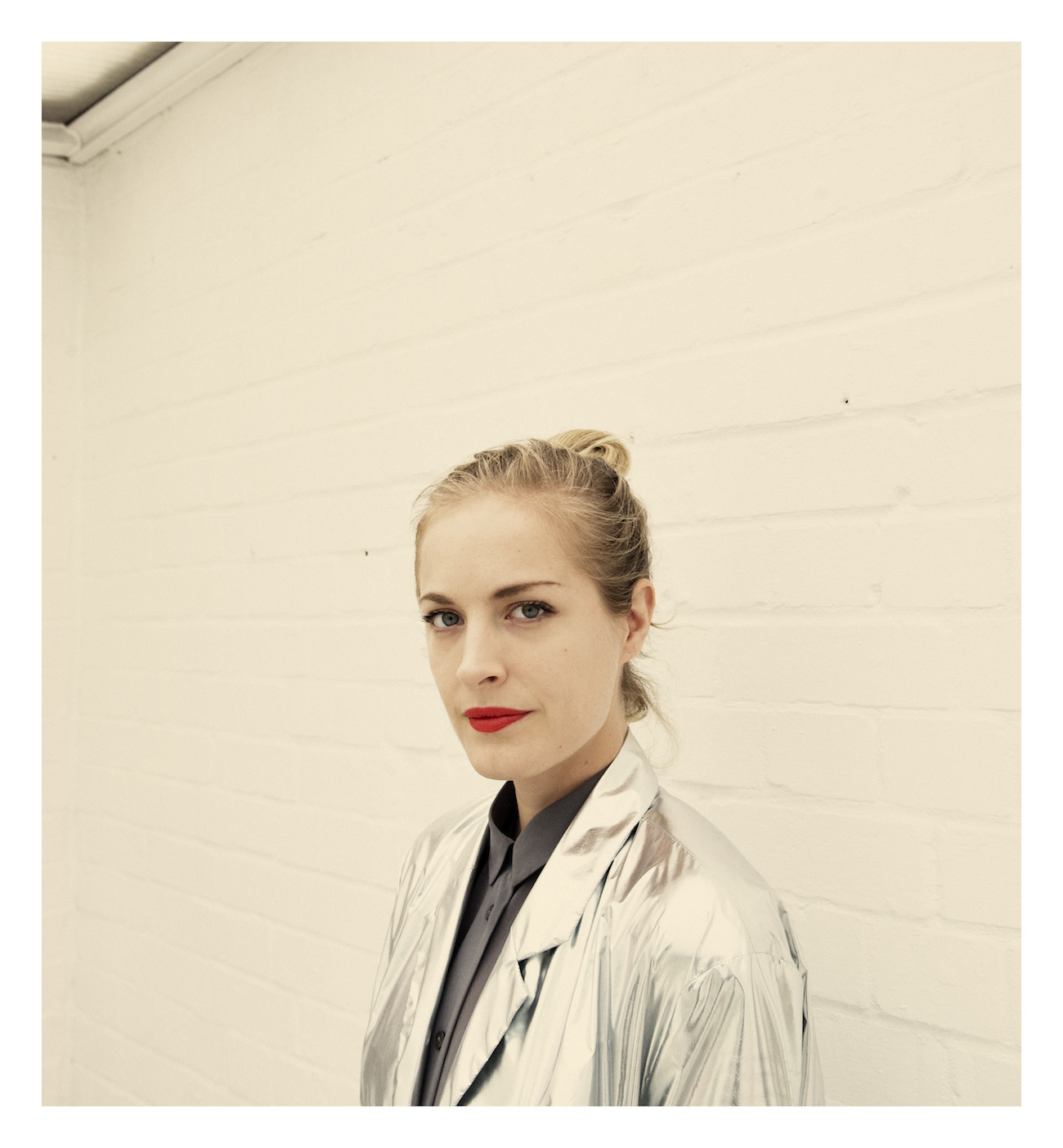

Born in Glasgow in 1981, and educated at Edinburgh College of Art, and the Slade School of Art, respectively. Paterson belongs to a successful crop of Scottish artists who have broken onto the international art scene in recent times. While her fellow graduates are still likely to be faltering over their second or third group show appearance, Paterson has established herself as one of the most precocious young talents to emerge in the last five years. With solo shows at Modern Art Oxford, UK (2008), Albion Gallery, London (2008), James Cohen Gallery, New York (2011), and BAWAG, Vienna (2012). Paterson moved to Berlin after graduating, from where she positively engages with a wealth of creative approaches that are less painting and sculpture, and more a cache of inventive mediums that turn her otherworldly interests into artworks. Paterson’s collected works are born of her wonder of such magnificent manifestations as cosmology and universal causality, and her investigative exercises can appear as sound pieces and atomized rock. That begin and end their journey in localised spaces (gallery and site-specific). Encouraged by a new wave of interest in planetary studies and global issues, Paterson has drawn our attention to timely subject matters that ground us all, and in so doing has delivered artworks that scrutinize the elemental value of our lives in time and space.

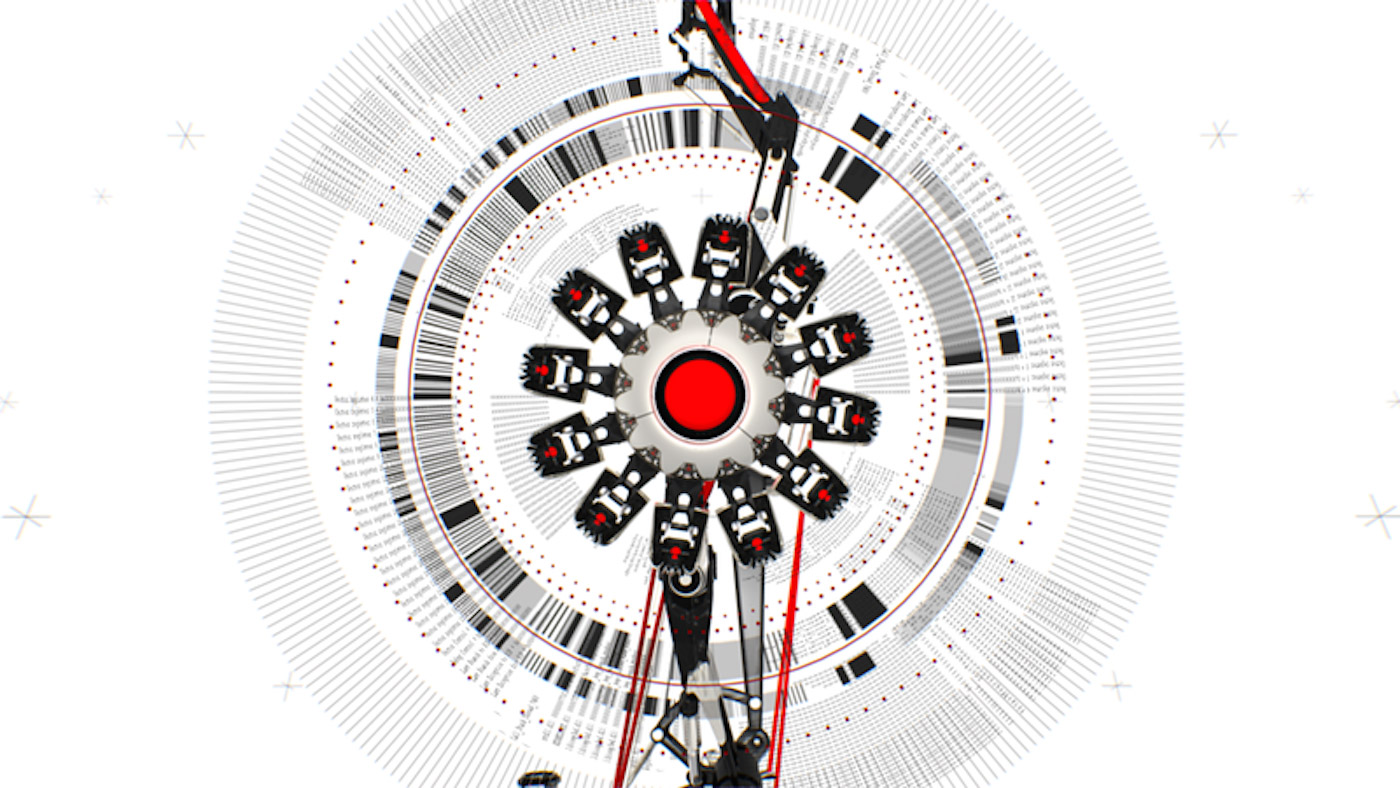

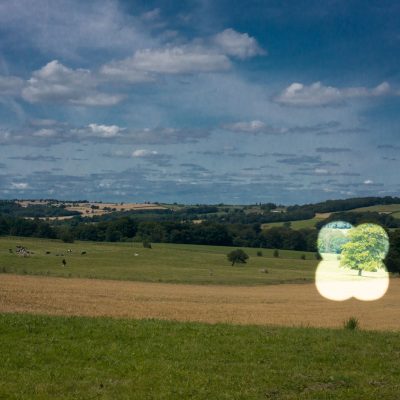

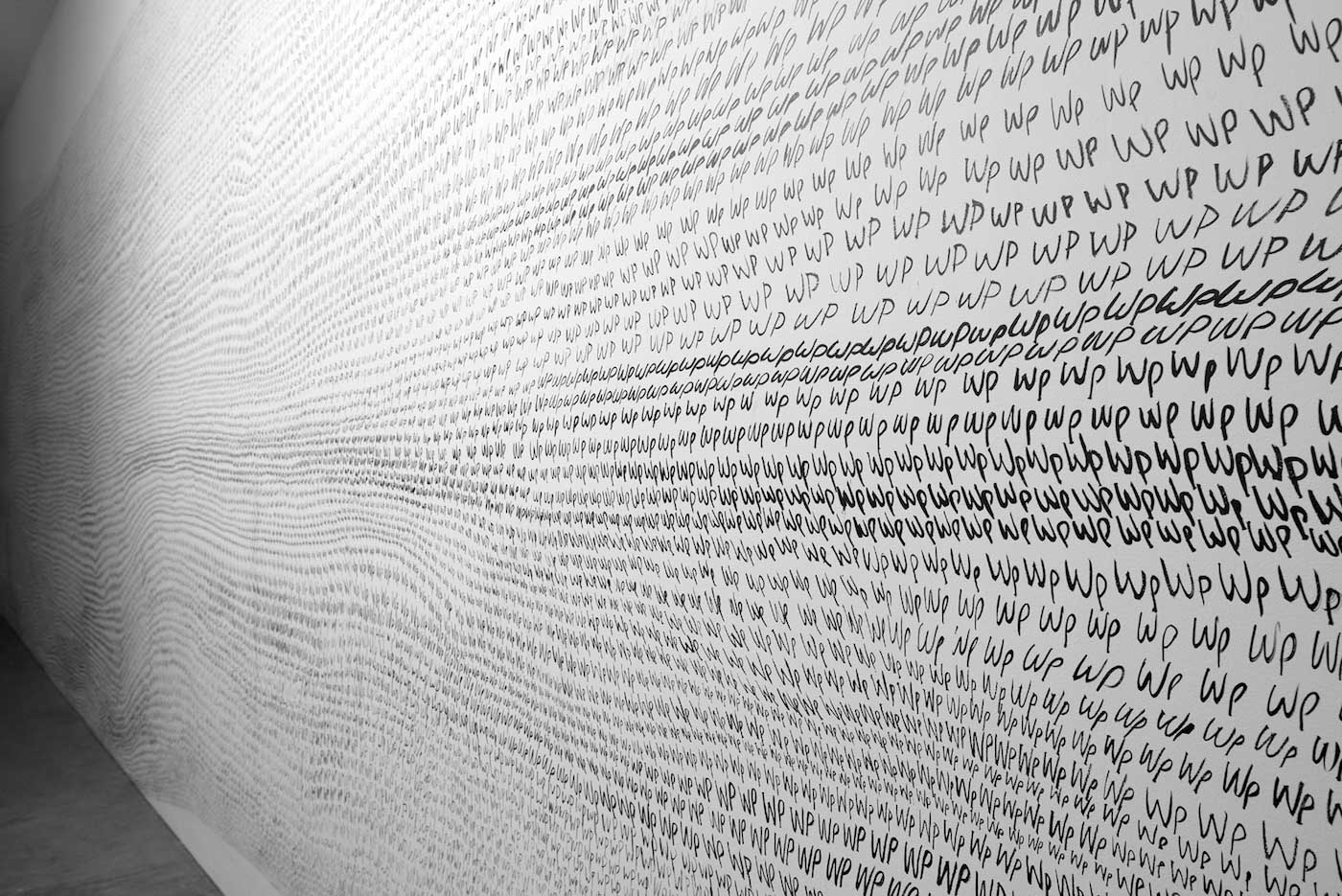

Leading works include All the Dead Stars 2009; which reads as a constellation of 27,000 known dead stars, that Paterson has had carefully laser etched onto black anodized aluminum. An artwork that reads like a blueprint of a sea of astrological fatalities in space. Inside the desert lies the tiniest grain of sand 2010, initially appears as utterly futile, but upon closer inspection becomes something else entirely. A work in which Paterson collected a grain of sand from the Sahara Desert, and using nanotechnology has it reduced from its original microscopic size to something even more impossible to see with the naked eye. The minuscule detail of this grain of sand was then returned to the Sahara and buried deep into the desert. And for all that what remains is a single black and white photograph of the desert, and a figure in the middle distance rising from a sand dune with an arm outstretched. A work that recalls Francis Alÿs’s 2002 work Faith Moves Mountains, (In which Alÿs recruited an army of volunteers in Peru, to move a sand dune several inches).

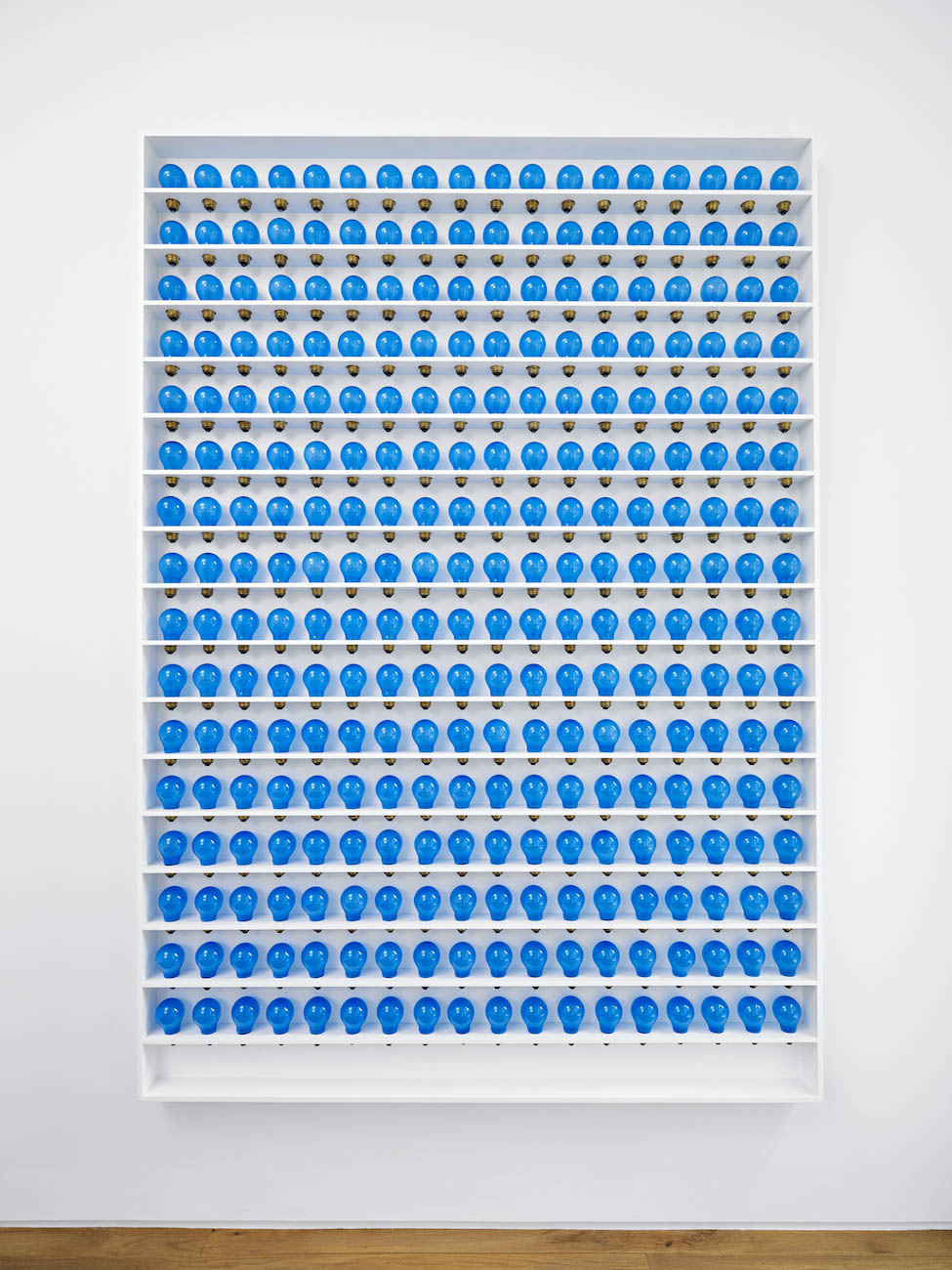

Another work Light bulb to Simulate moonlight 2008, appears as an impressive installation of coloured domestic light bulbs. That have been removed from an oversized wooden crate, which appears as part of the artwork. The bulbs running side by side within an open cabinet attached to the wall, in an amusement park styled display. The configuration of 289 bulbs, in which each bulb burns for 200 hours, alludes to the lifespan of a human being in relation to the light transmitted by the moon in a given lifetime. A ‘light’ and ‘life’ installation, the infinite calculables of Light bulb to Simulate moonlight 2008, proves like so many of Paterson’s work, that they are greater than the sum of their parts.

Rajesh Punj: For an audience less familiar with your work, can you begin by exploring and explaining your practice?

Katie Paterson: I often work with many different people to realise my ideas. My art practice is multi-disciplinary, exploring ideas relating to the landscape, geology, space, time and the cosmos; using technology to bring together the commonplace and the cosmic. Everyday technologies – such as mobile phones, record players and radios – connect with vaster, more intangible phenomena. The imagination always plays a key role. In the past, I have broadcast the sounds of a melting glacier live to a visitor on a mobile phone; mapped all the dead stars; compiled a slide archive of the history of darkness across the ages; custom-made a light bulb to simulate the experience of moonlight; and buried a nano-sized grain of sand deep within the Sahara desert. My studio practice is changeable and dynamic. I have a modest studio in Berlin, and two assistants. In the last few months our research has ranged from lunar chemistry, forestry, geology, clock making and horology, to paleontology and perfumery.

RP: When was it you first turned your attention to the world outside?

KP: I don’t think I’ve been attuned to anything other than the world outside. As far as I can remember, it has always been this way. Over the years and through learning via subjects like astronomy, it is becoming clearer that the world outside and inside are the same. The same atoms that were formed in the early universe pervade through the universe now; our planet is formed from the remnants of exploding stars from millions of years ago. These remnants and elements flow in our blood.

RP: You describe having ‘no particular interest in the cosmos’ prior to going to Iceland in 2004/2005, and definitely ‘not of a scientific mind’. What was it about the extreme environment there that altered your practice so fundamentally?

KP: Being in Iceland adjusted my perceptions and senses about living on, and belonging to, a planet that revolves around a vast star, amongst billions of others. It took being in Iceland’s otherworldly nature to remind me of this. Iceland is exploding and shaking with life and energy, the sun sets and rises in the same moment, the light continues through the night. Lava poured across landscapes evoke its evolution. I looked upwards and all around, and became interested in geology and time, the moon and the wider cosmos.

RP: You have termed your works ‘subtle and minimal’, and that you require the audiences ‘imagination to take a leap, and its where that takes you that matters.’ Is your work less about the idle act of looking, and more an invitation to engage with an idea?

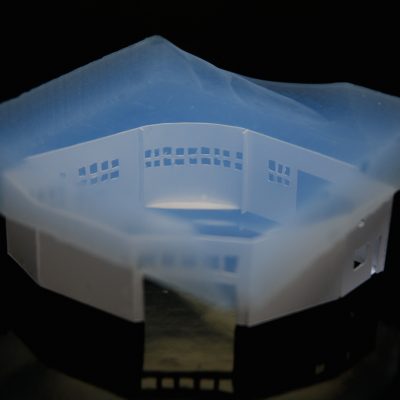

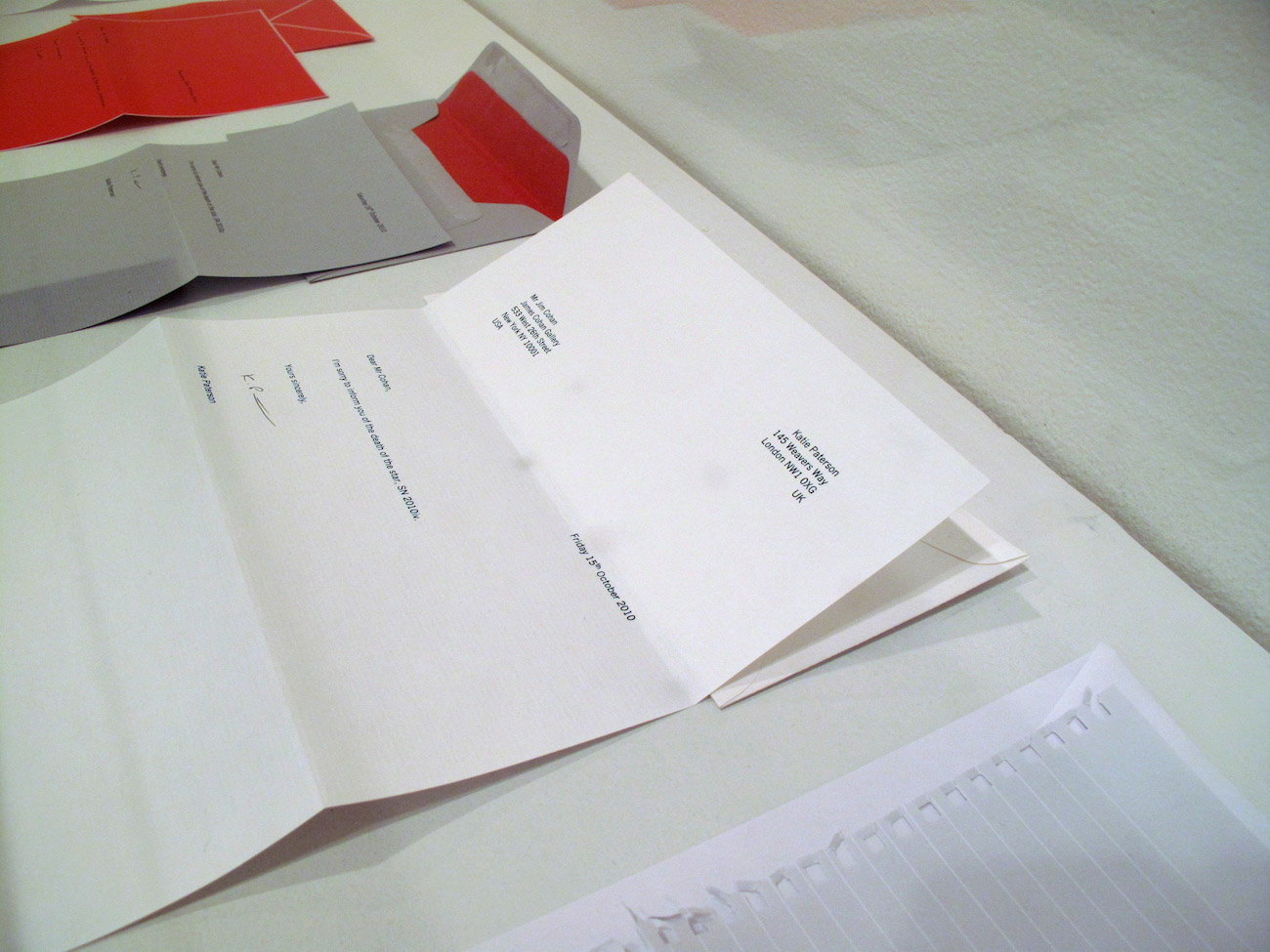

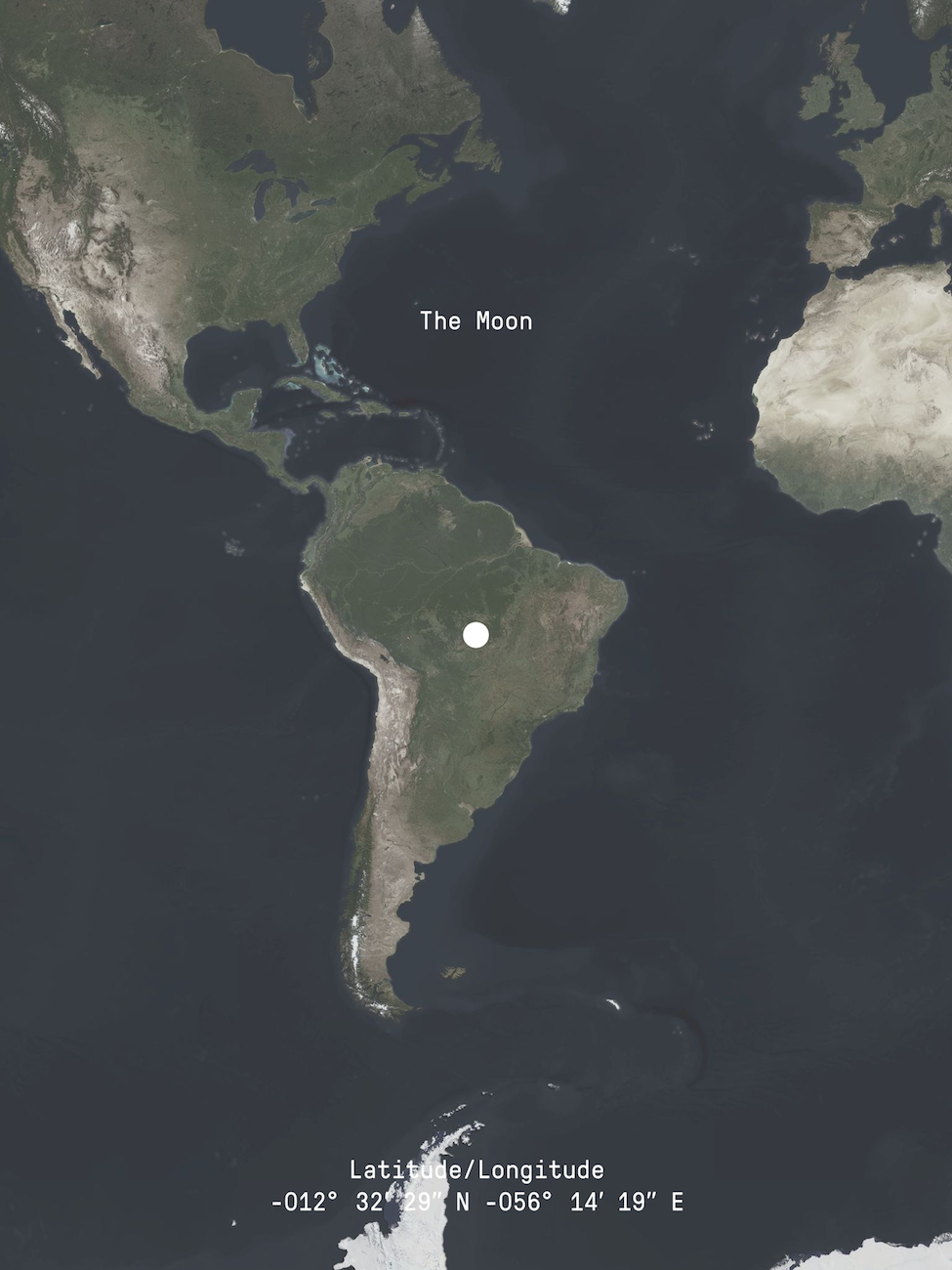

KP: First comes the looking, or reading in the case of the Ideas – Sterling Silver texts, haiku like statements – on show at Ingleby Gallery now. Then I hope, comes the transportation, to the place or image formed. Works like Vatnajökull (a live phone line to a glacier) or Second Moon (posting a fragment of the moon around the globe) involve real live processes, but much is unseen, perhaps only heard, or encountered through a simple tracking slip. The collapsing of space and time takes place in the mind, and the encounters are within the imagination. The minimal nature of my work is intended to leave no space for distraction, but plenty of space to take the leap into the day-dream.

RP: You appear fascinated by the elements, ‘on earth as they are in the universe’; how might we begin to comprehend the visionary ideas that you want us to experience, in the artworks and installations that you produce for us?

KP: I am fascinated by the elements; distant lightning storms on earth, explosions in space, weather on other planets, ancient fossilized forests. The elemental nature of the universe in the period after the Big Bang. Ancient Darkness TV looks back to a time in the universe where the first light existed.

A faraway meteorite was molten, recast, and then returned to space. The time is evident in the materials and alchemical process. Fossil Necklace charts the evolution of life across earth through carved fossils – trees, rocks, creatures, coal, coral, even fossilised rain. On the surface Fossil Necklace might look like a discrete and aesthetic object, but when probed further its dark side is revealed, the death and mass extinction of life repeatedly.

RP: How do you effectively combine ‘art with science’ so well, as has been written about you?

KP: I do collaborate with scientists – astronomers, lighting engineers, genetic evolutionists, paleontologists, to name a few. These collaborations are central to what I do. However, these fields of interest are not only within the realm of science. The matter, material, phenomena in my investigations exist around us, inside us, everywhere. My artwork follows from a curiosity about the world and universe, and sometimes this involves fields of science (examining gamma ray bursts, the temperature of moonlight, the time on other planets), but also philosophy (is there a time before the Big Bang?) literature (Future Library) and poetry (the recent Ideas).

RP: With your work resembling more of the scientific, has your studio become a laboratory from where you correspond with a whole network of scientists? And do you have a library of books on astrophysics, where other artists might have sketches and paint plied to the wall?

KP: The studio rotates from moments of order to complete chaos. I work best in a calm, empty, quiet space. However at times the studio does resemble a laboratory. During the development of Fossil Necklace for example, there were huge bones of extinct beasts, the thigh of an ancient mammal next to chunks of tree from Egypt, strange sea creatures and piles of fossil dust everywhere. The studio became an excavation site. We test things out in the studio, prototypes, models etc., it gets messy. There is a lot of communication too. When the studio was built I thought we had enough space for 10 years of books, but we seemed to have filled them already.

RP: It is fair judgement to say your works are ‘simple’ while they deal with the complex?

KP: I like to think that each of my artworks can be expressed in a few sentences, even a few words; laconic. My works aren’t intended to provoke a particular response, but function more like a butterfly effect, beginning like a shadow and rippling out, quietly. My own creative processes are quite similar. Ideas come, often through a process of writing, images appearing clearly, often in nano, milliseconds. The idea is discrete, described in a few words, and later if I’m lucky its ripples might catch up with me, and I’ll think about bringing it into existence. I hope the complexity is evident, wrapped up in the simplicity of the ideas.

RP: Words like ‘time’, ‘distance’, ‘transformation’, and ‘a sense of awe’, have been used to describe your work. Are you attempting to capture a vast matrix of evolutionary ideas in each of your works; that are of the earth and not of this earth at the same time?

KP: I like the idea that my work is ‘of the earth and not of the earth’ as the same time. Fossil Necklace brings together micro and macro worlds. Ancient ammonites carved out look like mini Saturns’. Planets of coral seas. Second Moon is hovering on the boundary between planet and sky, sky and galaxy, galaxy and universe. The thousands of pinpoints etched on the map of dead stars represent light that has travelled through the universe to earth, and the material from these stellar explosions combined to form earth. I hope my work has an ecology of ideas, forming connections between distant times, spaces, species, gaps, universes.