The Miniaturist

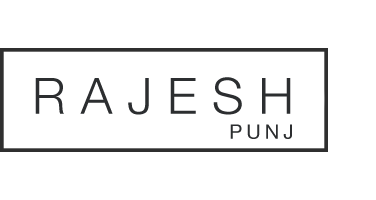

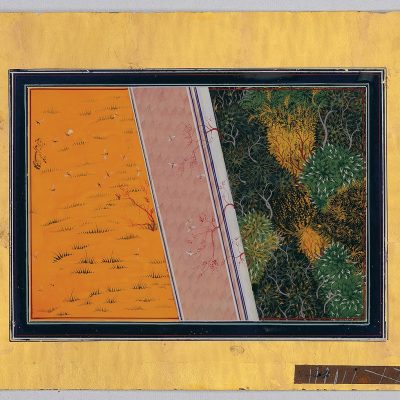

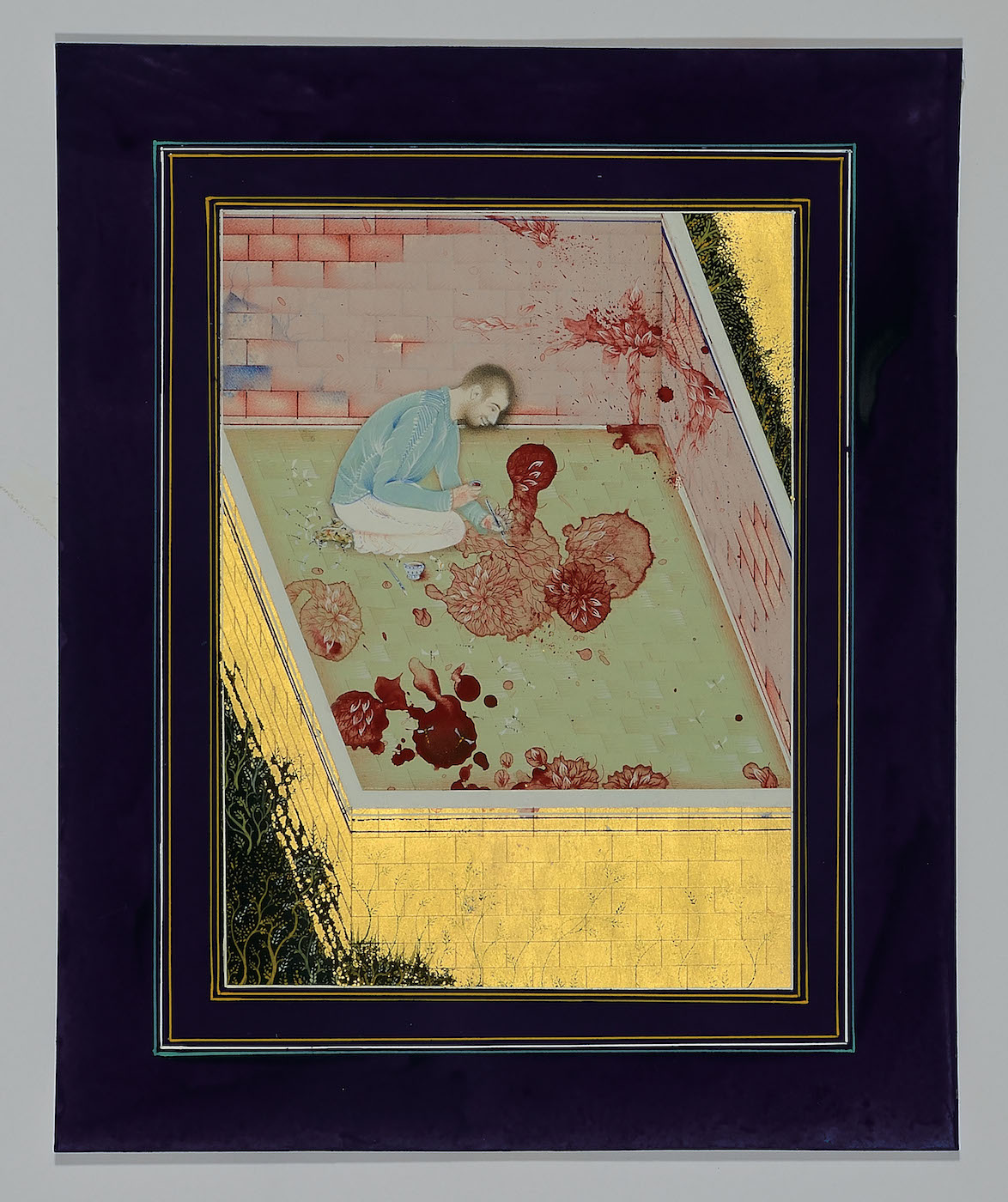

Imran Qureshi is at a point now where he possibly spends much more of his time hovering just above the clouds than he is rooted to earth. Softly spoken and looking exhausted for the all of the accumulated air miles under his belt, Qureshi is fundamentally a very honest and well intentioned artist, whose success he still has trouble comprehending. Describing the turning point as his Sharjah Biennial commission in 2011, in which he decorated the courtyard of the Beit Al Serkal building with the work Blessings Upon the land of my Love. Qureshi’s signature style of layering beauty over violence was heralded with his receiving the biennale award that year. Which in turn lead more significantly to his being recognised as Deutsche Bank’s artist of the year in 2013. Which like a monsoon led to a whole series of high profile shows at the KunstHalle, Berlin (2013), Museo d’arte Cotemporanea, Rome, (2013), Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst, Antwerp, (2013) and The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, (2013), in less than twelve months. Qureshi’s work is a combination of lashings of creative spirit, reeled in by pockets of miniature details that appear to anchor his work, and give it its cultural currency. And for Qureshi as reluctant as he original was to take on the style, it has proved the making of the man.

Rajesh Punj: Can I initially ask how do you work so effectively over so many continents and countries now? Do you seek to surround yourself with a team of technicians and gallery assistants?

Imran Qureshi: No I mainly work alone, I only take help when I am working on a site-specific floor or wall painting on a larger scale. Otherwise I do everything by myself, even managing my own studio. But now I feel like I need someone because it has become too much. But I have always been more comfortable when I am alone.

RP: Have you now arrived at a point where you can stop teaching and concentrate entirely on your work, and all of the commitments that come with being so critically successful now?

IQ: I think teaching is still integral to my work, it is something I have been doing since day one. And the college is very understanding of my needing to be in Dubai, Paris, London or New Delhi. And they let me, and even encourage me to do my own practice. Even if I am here I manage over there as well, constantly talking to my teaching assistant. And they are always informing me that this thing is happening in the class, and of what to do regarding that.

RP: So originally you began as a miniature painter?

IQ: I was trained as a miniature painter at the National College of Arts, Lahore in 1993, and as a student I realised there was a point where I had to choose an area of specialisation. So I chose printmaking as my elective, and painting as my specialisation; not choosing miniature painting originally at all. But then my lecturer who introduced me to miniature painting in my second year at the NCA, he persisted in telling me to take on miniature painting as a practice. He said ‘you can do it and you can be very good at it.’ And I said no my temperament is very different. I was very social and into performance at that time. I was originally doing performance based theatre with other students. And of course miniature painting was something that was very demanding.

RP: I assume with miniature painting there isn’t the scope for being as spontaneous as you would have wished to be?

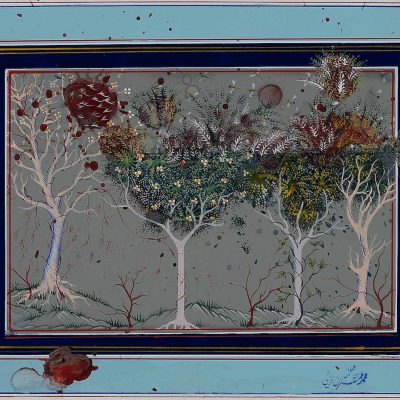

IQ: Yes but for me it became a curiosity, a calling if you like; having been almost coerced into choosing miniature painting as a professional practice. I thought I should give it a try, and I took it as a challenge. There is a general perception about miniature painting that it is only about reproducing existing miniature paintings. That it is entirely about the craft of reproducing a work, and about a standard technique. And that under such circumstances you cannot express yourself as an artist. But for me when I decided to engage with and become a miniature painter, I decided to break away from these pre-conceived ideas.

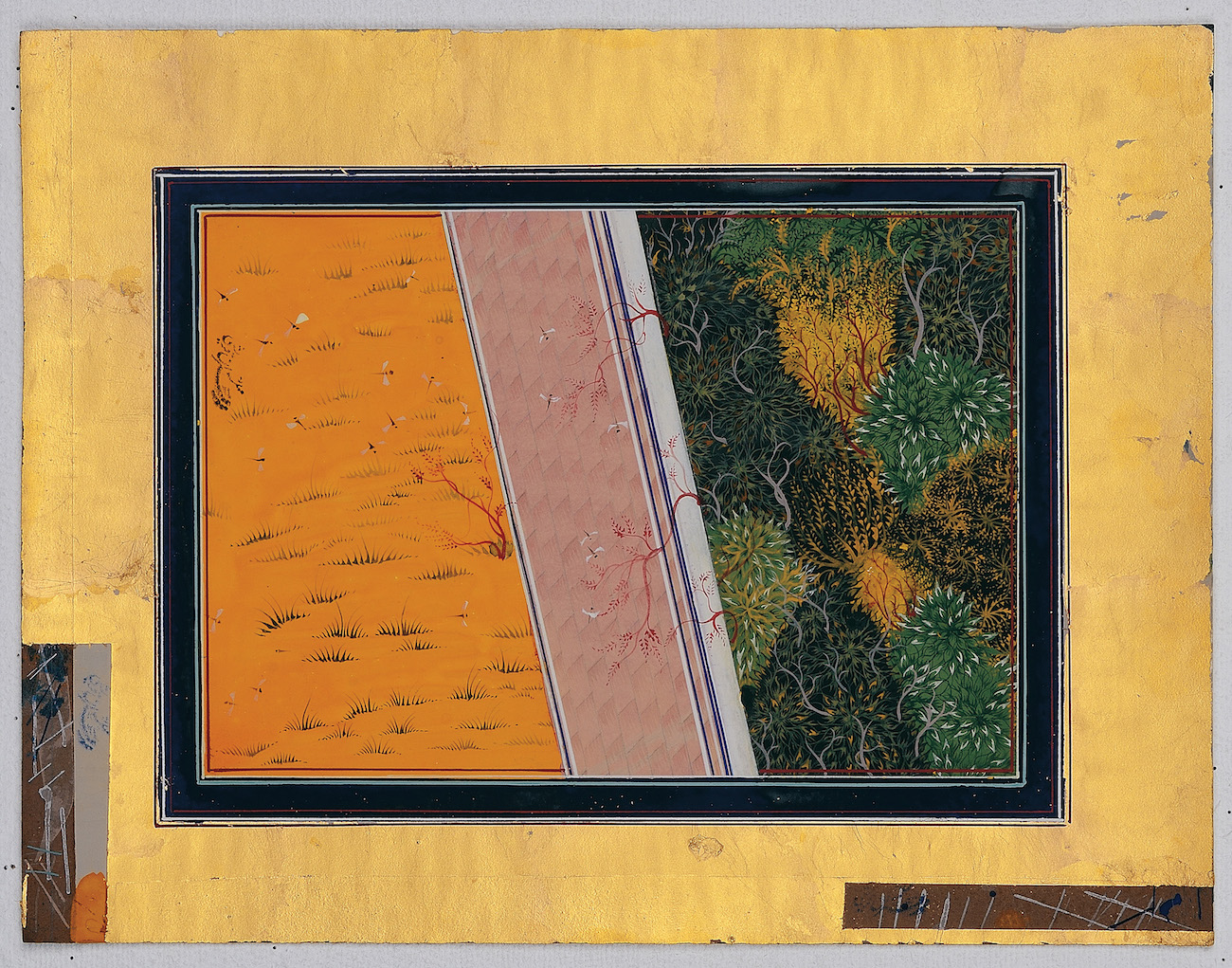

RP: So you decided to introduce contemporary elements to the process of painting?

IQ: I kept asking myself what contemporary miniature painting might be, and I tried to find an answer through my art practice. So possibly it wasn’t entirely about introducing something new into miniature painting, it actually happened very naturally. The academic training at the NCA was very strict and incredibly disciplined, and I learnt the technique with a certain kind of understanding, and then when I was doing my own work I was free. It is in my blood, so now even if I am doing a rooftop commission or a miniature painting, there is a connection of two very different things.

RP: In terms of miniature painting what was the next step for you, because obviously now when we consider your work, the scale of the works have become monumental. How have you so effectively made such a shift from the minor to the major?

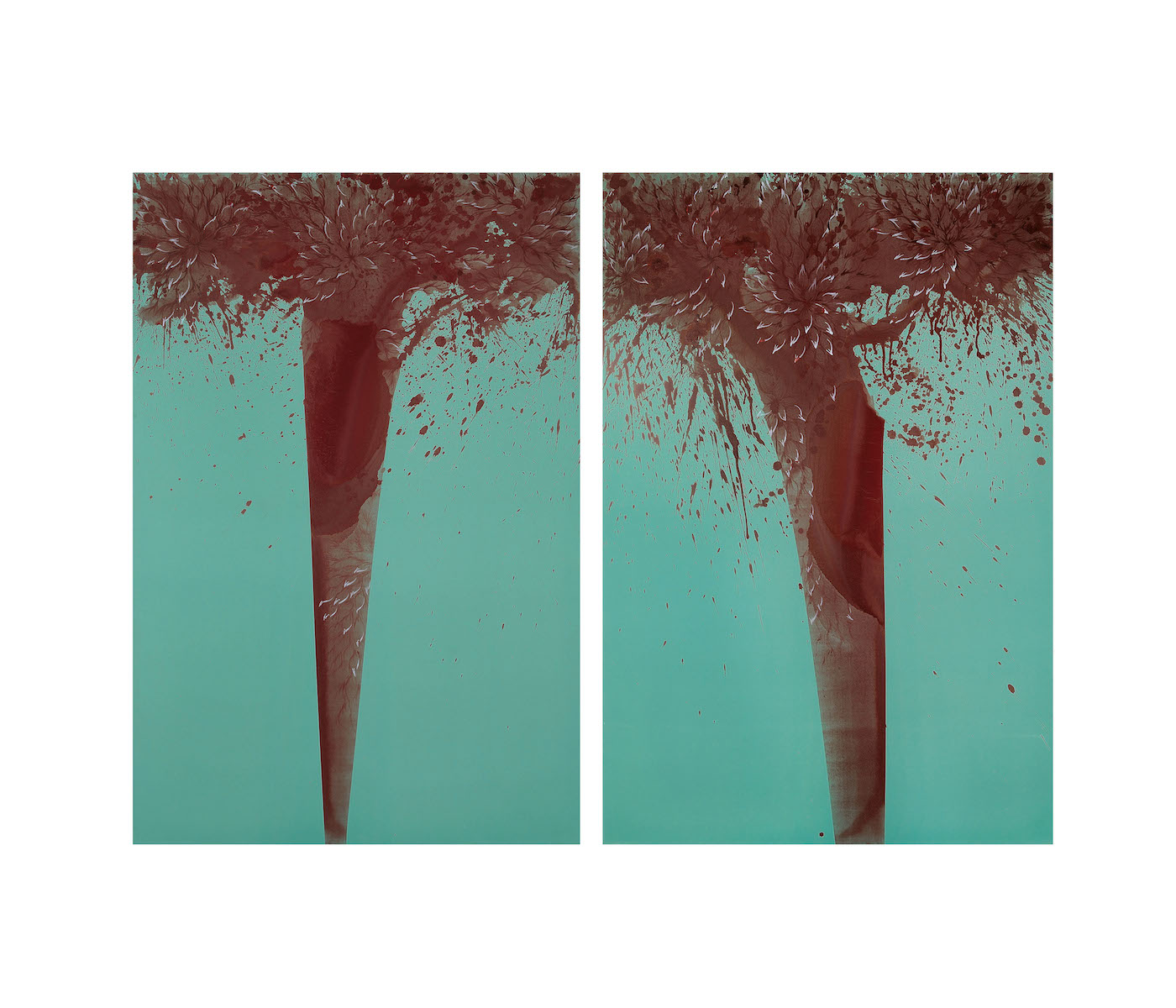

IQ: That goes back to my interest in performance that I mentioned earlier. I was always interested in contemporary painting, and in mixed media as a student. So I think for me whether I am making a small miniature or a giant installation, they are one and the same. I can easily comprehend both, even with issues of differing scale and size. Because it is in my nature that I enjoy such challenges. And with a major show I don’t wish to plan too much of it, because if I do follow certain guide lines and stick to a predetermined plan, there is no excitement in it for me. For the forth-coming Ikon show in Birmingham, the original idea was to bring the And they Still Seek the Traces of Blood work there, and I suggested we remove some of the work and I decided to introduce a new element to the work for the show.

RP: So what of the works you are currently working on now?

IQ: There are different exhibitions coming up. My work is in the Manchester Triennial, which has just opened; which includes collected works from my gallerist Corvi Mora, as well as from other collections. And then there is another show in Toronto at a new museum called the Aga Khan Museum, and this will be the inaugural show of the museum. Interestingly they have their own collection, which is Islamic art, where I will be exhibiting with five or six Pakistani artists. I am making new works for that, including miniature paintings, plus a site-specific piece in the gardens of the gallery. I am also planning to show my new video works there. I am making two when I return to Lahore, and then two are already on exhibition at Rhode Island, New York.

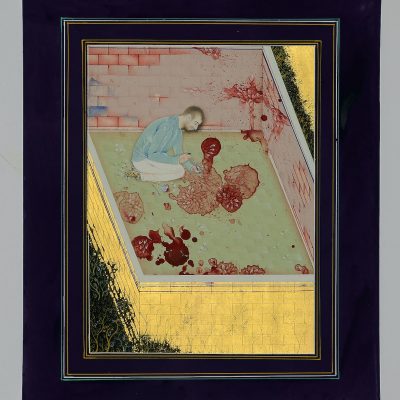

RP: The pièce de résistance for me are your monumental paper installations; And they Still Seek the Traces of Blood, a version of which was in Antwerp. What are you attempting with that work?

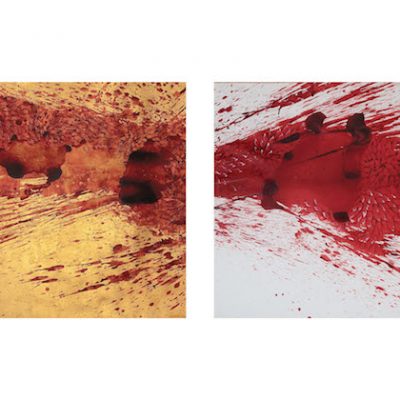

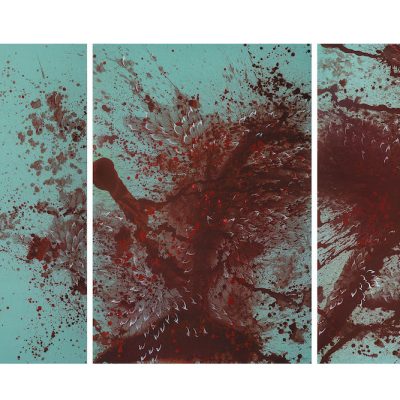

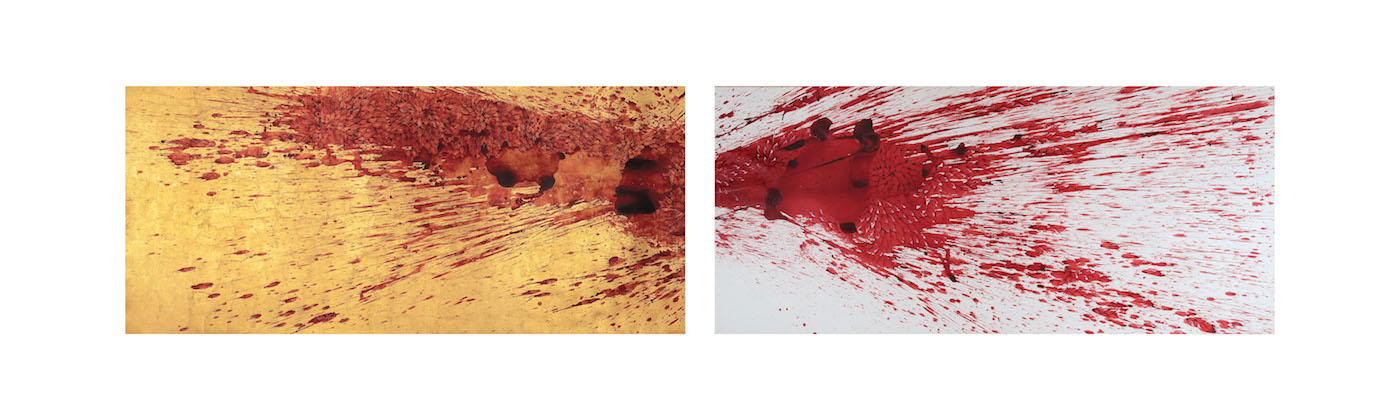

IQ: That is one of my favourite works too, and it will come to Ikon, Birmingham in November aswell. Essentially the work is made up of different images of previous installations I have completed. At the Macro Museum in Rome, the work was made up of images of the Metropolitan roof top work, with photographs of the details of that. And I had those details printed up on both sides of a thousand pieces of paper, and then it is rumpled up and already coloured, so it looks like meat or flesh. And the red colour comes from the print itself. So when you construct it you transform it into something. So I originally used the architectural plans of the Sharjah court yard in a show in Lahore and again in Berlin; and then I used images of the Metropolitan Rooftop at the Macro Museum in Rome and Dubai. And more recently in Michigan I used the Metropolitan rooftop again; but in Mukha, Antwerp, I used my recent installation from Michigan.

There are six different images in total, with details on both sides of the paper; and there are more than twenty thousand sheets of paper in total. The work is built up systematically, and the basic shape is constructed. But out of twenty-eight thousand sheets of rumpled paper, if twenty sheets fall down, I can live with that. You cannot stop something from happening, even if someone wishes to touch it, and in a way it is about the audience investigating the work as some kind of incident. Because the original idea was about how an incident can happen on the street, and it is the ‘common people’ who suffer the most. And immediately afterwards the common people are asked to stay aware from the site of the incident, in order the authorities can be allowed to investigate what has happened. And as a consequence you don’t get the whole story. So the work becomes about the audience, who can’t touch it, or investigate it. And the work becomes traces of an incident or an event that has happened previously.

RP: On the nature of the temporality of your work, have you been commissioned as yet to create a more permanent work?

IQ: No, nobody as yet asked me, and it would depend entirely on the space. But there are two elements that are always consistent in my work, whether I am doing miniature works or larger scale work, to do with violence or beauty. In order I can create loosely defined marks with carefully drawn images; and a place, space, city, will always add something new to that mix. And it can be in a subtle way, but it does allow for something new every time. For example the paper installation, the first time And they Still Seek the Traces of Blood was first shown in Lahore, and then it went to Berlin, the display was entirely different because of the nature of the space there, and of the facilities and everything there. And again at the Macro Museum in Rome, it was completely different again. The layout was more like lava melting and coming down and creating a landscape. And for the Ikon it will be a variation again. It is always very subtle and very slight, but I will add something new to the work every time it goes somewhere else. And it is always about the work and how it sits in the space, in order it can have a strong dialogue with the audience. And the works are always about the human experience.

RP: But I guess that’s the nature of the beast, of your international success allowing for one show after another. Was Deutsche Bank’s recognition the turning point for you?

IQ: No the turning point for me came earlier with the Sharjah Biennale, and of my installation over there; and it definitely made the world look at my work. I never expected that. People were telling me that the award for best artist was for me at the dinner. And I was asking why am I going to get it? Why should I be chosen over everyone else? And when they announced my name I was more interested in my fish supper than anything else. And that was the moment, and the response was so powerful that it was a very different experience from what I had known before.

Not just from the curator, gallerist and museum people, but from the common people who were coming to the show. And everyone was relating to the works immediately. Some people in the audience were actually crying. And they were saying this is the first time that a work has made us cry, actually cry.