Killer Beasts

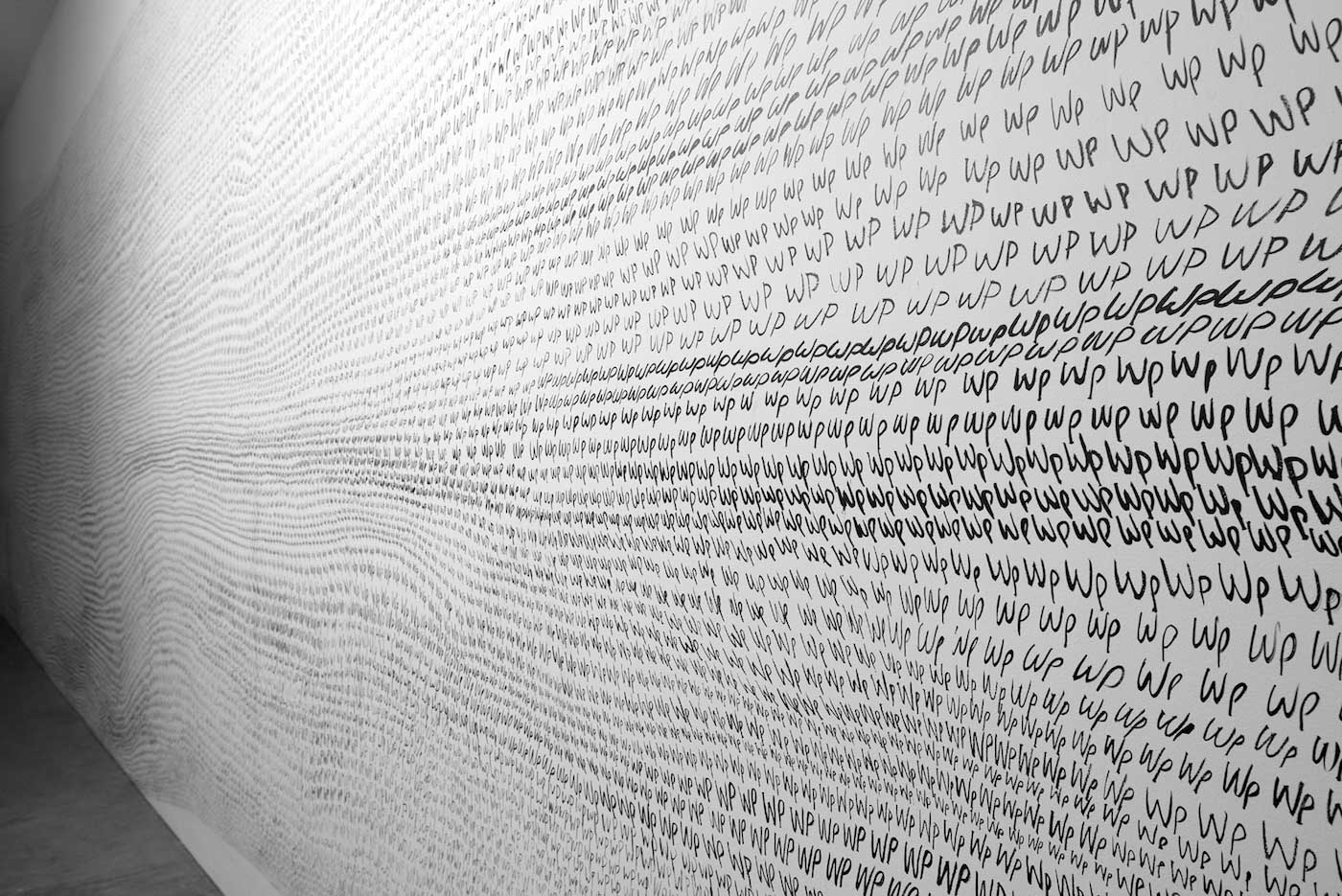

From the North of England, Fiona Banner was born in 1966, and attended Kingston University in the late 1980’s, before going onto Goldsmiths College, London in 1990. She had her first solo show at City Racing; (1994), an artist run space in South London. And in 1995 was included in General Release: Young British Artists, at the XLVI Venice Biennale. Following solo shows at Neuer Aachener Kunstverein, Germany, (2002) and Dundee Contemporary Arts, Scotland, (2002) Banner was nominated for the Turner Prize in the same year. Renowned for her visual fascination with military aircraft, her rendering of macho American war films in text based installations; she is intentionally engaged to a milieu of cultural contradictions. And as a publisher and artist Banner explains of her ‘interest in the voice of language, and the mistakes of language. Yes the high points of it, but also in the hopelessness of it; and how we always come back to it.’ Banner has exhibited extensively internationally, and has a forth-coming solo show WP WP WP, at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, UK, (2014).

Rajesh Punj: Is the Chinook helicopter still operational?

Fiona Banner: Yes it is hyper active, they came out in the 1960’s, and is the longest serving helicopter. When you talk to people in the military, they talk about this helicopter with some kind of mythological status. And for me it’s the way the blades always look like they are going to crash into each other. Because they actually go in opposite directions and cross over.

RP: So is that relative to the installation you have planned for Yorkshire Sculpture Park this year?

FB: It is yes, so the installation at YSP is something I have wanted to make for a long time. It is sort of a sculpture without a centre, because there is no body of the aircraft on display, it is just the helicopter blades rotating in the space between zero and 45 rpm; so at times quite fast. And they will be choreographed; so there will be a structure to the pace.

RP: And is that comfortable for an audience, entering into the space for the first time?

FB: ‘Comfortable’ is an interesting term. I don’t think it will be comfortable, but I don’t think it will be totally intimidating either – disquieting perhaps. It will have a strong performative element. For me I am used to relating to these aircrafts from a distance; and often through some mediated form, in movies, newspapers, you tube, images generally; or way off in the distance flying over London. So just to be there up against the functionality of the aircraft – the blades in action presents a weird proximity, it’s a strangely emotional encounter

Chinook helicopters are not available, there are not very many of them in the world, and when they are, they are stripped of all their high value assets and cannibalised. So maybe to focus on the function of the blades comes out of that, as a sort of sculpture in absentia – also for me it is the part of the helicopter that speaks most eloquently of contradiction. In the way that they work; the way that they go against each other in opposite directions, it’s ‘a push me, pull you’. The blades appear to collide, because they cross over, so there is an incredible power in how they work, and how they appear but there is also great vulnerability. And I am interested in the image of the helicopter as well, because it is so animal like, it is so inelegant, dinosaur like, and yet it performs an incredible dynamic function, and is technically very advanced. Something primitive, something sophisticated – something that pulls you in opposite directions, it is associated with super serious stuff, but is almost comic.

RP: The Chinook recalls the other modern aircraft you have used as artworks, including the ‘Harrier’ and the ‘Jaguar’; why have you selected those particular combat aircraft?

FB: With the Harrier and the Jaguar (Tate Britain, 2010), I really wanted to work with aircraft that were still in service; so both those models when I displayed them were still functioning in the military, and were of a type and still had a currency in their field of conflict. It was important for me that as viewers we were implicated or inevitably part of these objects, if only through the fact of being contemporary, or of having contributed to them as tax payers… So an old aircraft, a retro imperial war museum type thing is of no interest to me. Somehow that would seem romantic, and I am not really interested in being romantic. Though I am interested in the seductive qualities of these airplanes.

RP: How did you determine the compositional layout for works of such magnitude?

FB: Those pieces were quite specific to that neo-classical end of empire space of display at Tate Britain. The museum was never designed to accommodate major industrial scale military hardware; it was designed for sculpture and painting. Specifically sculpture I think for those outer spaces, but of a very different scale. The planes only just fitted the space. Someone describes them as looking ‘exactly wrong’. The Harrier looked captured, it had the sense of it being a trophy. Like a hunter might hang a dead bird. Again they were anthropomorphic and had association with the primitive and nature, through their names for one. But I was also really interested in pushing our voyeuristic tendency to those aircraft.

RP: How did your large scale text pieces come about, referencing films like Top Gun, and Apocalypse Now?

FB: Well Top Gun (an intricate blow by blow account of that film in words) (1994), and Nam (1997), (which is a book encompassing six well known Nam movies, written in my own language); those early verbal works did come out of a particular engagement with main stream movies, and how they try to, and often do, reflect, and in turn affect how we see things. So to take Top Gun, I got really into that film, and I was intrigued by it being such a basic film. It comes across if you like as a trite piece of fiction, mainstream Hollywood, and as an unreflective bit of entertainment. But what interested me in it, was the really euphoric, almost splendid display of flying, how they displayed the kudos and muscle of the fighter planes. And how it came out right at the end of the Cold War, so it was a way of displaying these aircraft that hadn’t had a run for their money, using them as active elements of ideological conquest but imbedded in this dump text, which is in many ways just a courier for displaying the military hardware – but one that pulled certain emotional triggers.

I was making paintings of the film, and of the aircraft in it – they weren’t terribly good paintings, because I was very messed up about what to keep in, and where the frame was – so I ended up in an editorial malaise, and finally ended up making these paintings where the aircraft left the frame, they were virtually monochromes. And at that point I thought I have just edited everything out of this painting. And at the same time I recall I was reading a lot about photography, and the stories about how photography is manipulated. I suppose it was (Susan) Sontag, (Paul) Virilio and all that sort of thing, which questioned the validity of the visual as we known it.

RP: Which brings us back to the intended contradiction in your work; because these works are so labour intensive. You are scrutinising a film that the majority of us have seen as teenagers and handsomely forgotten about. Why labour over such ‘low level’ culture?

FB: For one low culture is the dominant culture. Also I wouldn’t say ‘intended contradiction’, but ‘active’, yes – because I’m working with a personal contradiction too – I was seduced by those films. Using words was a way of working with them without using the image directly. As for the process, there is something immersive about making that work and that went also with the process of looking and reading, of duration. As a practitioner that engagement is a positive thing, as an artist you have to somehow engage with a medium, in this case it is written language, you have to hinge your thought to something tangible, however ephemeral, or physical.

RP: Your works appear ‘wonderfully complex’; is that your intention?

FB: No. But I don’t want to simplify complex things either, and finding a way to do that is often what directs things.

RP: Should there be an introduction to the work Mirror; it is one of several other films works at Yorkshire Sculpture Park that kind of comes out of the blue?

FB: The film (Mirror, 2007 (in which the actress Samantha Morton performs a description I made of her naked) could be a traditional life-drawing turned on its head, and it’s incredibly simple in many ways. Though it is odd because she had not read the description before you can see her encountering her own image as she reads it, and it becomes kind of overwhelming for her – you can see a struggle there. But through a series of situations I ended up with a work that said something about the absurd, unrequited sometimes desperate need we have to understand our own image, whether it is looking at images of other people or trying to make images of other people – and how we are somehow held to that. And the nude is perhaps looking at the human in a raw state, our obsession with the nude also reveals vulnerability in how the sexes relate to each other, and how we pre-empt how we will be related to, therefore it motivates a reaction that may create a further reaction. I don’t want to end up trying to satisfy your original question, and say something I don’t really think, but I suppose there is a narrative of complexity and contradiction around the work. Is it leading to any conclusion?

No. Is it asking some questions and then looking at those questions in another way? Peeling down the layers of expectations, so maybe you end up at a point where you are down to the bone. So something is sort of raw, and laid oddly vulnerable, or bare. But it’s not like I am formulating a position, as a practitioner, and intellectually nothing is conclusive. An idea develops, and it can take a very long time to turn into something – sometimes too long, and it never materializes. But I do often come back to things that I thought maybe had gone, I mean the themes do circulate.