Author: Rajesh Punj

Harper’s Bazaar Art, Manchester Triennial Review, Cultural Confederations

Building a Foundation – Lekha Poddar interview

In terms of everything positive that is of the contemporary Indian art scene now, then Lekha Poddar is its tour-de-force. Demonstrative and equally demanding of what she expects of those around her, Poddar’s original interests, fashioned by her son Anupam Poddar; appear to have expanded well beyond the visual arts and into the realms of cultural diplomacy. Based between Gurgaon, (Delhi), and London; and with an eye on the art scenes in Lahore, Tehran, Karachi and Kabul; the Devi Art Foundation’s attentions are as inclusive of the regions immediately outside of India as humanly possible. Outspoken in her criticism of the infrastructure for the arts in India, Poddar is fully aware of what is and isn’t working there. And rather than letting things take care of themselves, she is known for positively lambasting the art establishment of which she is a part. Responding to India’s Venice Biennale absence last year, Poddar forthrightly commented that before we think of going on to global platforms, we need to get our house in order in India. Accusing the powers that be of infrastructural failings that have allowed for a climate of inertia. Leading the way with a creditable alternative, the foundation appears to have gone from strength to strength, and in five years they have managed to amass a vast collection of works of immeasurable significance, from the early and contemporary periods.

Harper’s Bazaar Art: What is happening outside of Mumbai and Delhi in India in terms of art now?

Lekha Poddar: Bangalore, Pune, things are happening there, Kolkata as well. Not a whole lot happens but there are two people, Abhishek Basu (of Abhishek Basu Contemporary), and Prateek Raja of Experimenter Gallery, both in Kolkata, both are doing amazing things. And I think Prateek is very important for the contemporary scene, because I think what he is doing is really path breaking. Sitting there in Kolkata with no cliental, but selling to the world, and establishing a really good global reach. Really taking up artists who I am not saying would not be taken up by other galleries, but I think he (and his wife Priyanka) picks very carefully and he picks very well. And the artists are not all based in Kolkata; they are from Bangladesh, Pakistan, of course Indian, and some are in Kolkata. I think (Prateek) is really amazing. It is one of the best gallerists in India at the moment, and I do think he is truly brilliant. Mort Chatterjee and Tara Lal have also done what other galleries have not done, introducing performance art before anybody had even though of it.

HBA: Does that come with greater awareness of the contemporary European and American art scenes?

LP: I think a little yes; I think otherwise I find that the Indian galleries unfortunately are really lacking professionalism, and they are not pushing boundaries. Some are taking care of their artists; this that and the other. But basically it is all about the market, rather than creating a market. You can say, ‘I am following the market, so what do I do if so-and-so doesn’t sell’. But it shouldn’t be about creating a great deal of hype over an artist in order to create a market for them. If you look at their practices and guide them, that proves better in the long run.

HBA: That appears to be an enormous infrastructural issue with how the arts are managed in India; is that the case?

LP: I think so, very often the artists don’t like very much conversation, and the gallerists won’t have that conversation either. And if we want to move forward, developing an artist and providing them with a platform is a very important part of the art world. I mean gallerists should guide their artists, criticise their work, and also agree with their work. Give them a direction as to what the market would like, or discuss the next sets of works. I think it is very important, but unfortunately I am not sure enough it is really happening.

HBA: Is that to do with the more established gallerists thinking entirely of art as a commercial enterprise, and not as a vocation with a long view?

LP: My judgement is that from the turn of the century there was a very small market (in India); the artists and the gallerists had a great camaraderie, and they were all friends. But the market was small then; a small market with a small number of collections all with manageable prices. And then if we move forward fifty, sixty, seventy years; post two thousand, especially post two thousand and four, the boom came. And I don’t know if the gallerists even realised how to negotiate that whole thing. Everybody was so happy selling, and the artists were so happy selling, but nobody; possibly one or two did, but by-and-large nobody got into that stage of conversation between the two, (the gallerists and the market), of what to present to the market.

HBA: Are you suggesting at the time gallerists were collectively unable to discuss what was happening among themselves, in order to seek a more sustainable infrastructure for the arts thereafter? And can that be blamed on a climate of cultural selfishness in India that is more damaging to the arts than anything else?

LP: I think in India that is a problem, a huge problem, everybody wants to do their own little thing. And it is something to do with our DNA possibly, I don’t know if it is the same with the Chinese, the Malaysians or Indonesians, but I think that is an Indian characteristic across the board, and across any field. Unfortunately it is in our DNA.

HBA: Has this kind of cultural selfishness acted as an achilles’ heel for the contemporary art scene in India?

LP: I am saying that I imagine all of this is a western import. All of this, the idea of the ‘museums’, and ‘gallerists’. So I feel that over post-colonial India that that legacy carried on, and as I was saying the original market was very small to begin with. Those few galleries and artists interacted, because there were about ten collectors. There were really not that many, and the artists’ base was also small, there might have been between fifty and seventy artists all over India. Others were preoccupied with small things that were not particularly relevant. And then this explosion of contemporary art happened in a period when India was opening up economically; and they (western collectors and gallerists) created a market driven economy, and obviously the art was simultaneously market driven. So I don’t know if everyone has even had the chance to sit back and even think. And also more significantly because we have no critics, (which we touched upon earlier), we have no critical writing. So unfortunately it became a free for all. Because there is nobody to give a decent review of any exhibition, or there is no one who knows enough to even criticise it. So until someone gets into that whole thing, and brings it out into the open, we will continue to suffer for it.

HBA: Does that not require a great deal of honesty on the part of gallerists, dealers, collectors, and artists alike in India?

LP: Beyond honesty you need to know, you yourself need to know. Otherwise everyone is living in a vacuum because of there being a lack of everything to sufficiently support the arts in India. I think in India because gallerists don’t take the initiative to guide their artists enough, the artists themselves in their mid-twenties, and early thirties begin to think they know it all. ‘I don’t wish to listen to the nonsense that these external people are saying’. But fundamentally if there were people who knew their art, and the art scene well enough, in order to make it clear that this is what is happening around you, and if this is your kind of art then this is the kind of direction you should take; then they would possibly listen. Somebody has to be authoritative enough to do that, and it depends as you said on art schools, and art education taking a lead.

HBA: I remember the damning statement you made in Art Newspaper this year, aimed at those responsible for Indian art internationally; after it was confirmed there would not be an Indian Pavilion at the Venice Biennale last year. And I quote ‘Before we think of going onto global platforms, we need to get our house in order in India. To have a dialogue on public/private partnerships, we first have to strengthen our (art) academia, curatorships, critical writing, cataloguing, displays and so forth. How are we going to sustain the top of the pyramid when there is no base?’ Do you still believe that to be the case?

LP: I still maintain that. Why start at the top of a pyramid when we don’t have a base. Obviously the Venice biennial is very important, and of course we should push ourselves to be on an international platform. But I also feel that there has to be good curating for that to happen, that there has to be good backing. Artists have to be chosen very carefully, and it should not only be about artists who are market led. You know you really do need to have a whole critical appraisal of the art scene, and I agree in India it is happening slowly. We have the Kochi-Muziris Biennale which has been hugely successful, and I am pretty sure the next one in December 2014 will be a shade better. So a very small base is being created. The (India) art fair is serving a purpose I suppose in a very small way, yes they have huge footfall because the population numbers are so big. But very definitely until we get educational institutions correct, until we get people who become slightly more professional; and I refer to the gallerists and the artists, and until we have proper reviews and sound criticism for the arts in India, we are always going to be in this state of flux.

HBA: Therefore it becomes even more imperative for everyone to empowerment themselves, in order those involved in the arts can have a more informed debate. Clearly that’s not happening fast enough.

LP: In today’s world it is so easy via the net to see what is happening in the world. Even the generation of artists who started in the mid 1990’s, possibly for ten years of their lives, they had access (to the internet), but not such abundant access. Today everything is a click of a button away, so whether you are there or not there, if you are really interested in learning and knowing, you can actually just do it from your room. You have to want to be curious, and you also need that kind of inquisitive mind to say I want to know more.

HBA: So in terms of the Devi Arts Foundation, located just outside Delhi; what was the catalyst that lead to you acquiring works of art, and that then becoming something more substantial?

LP: Well as far as buying art was concerned in the mid-eighties, matching up with friends, I used to buy, but never thinking it was ever going to become a collection. And we then made a new home in 1998, and my son Anupam who had just returned from university met Bharti Kher, and he initially kept saying do you mind if I buy art of my generation. He ventured on, and basically started the collection, and then would nudge me after a year or so and suggested why don’t we do this together. And it involved art which to be honest I didn’t understand initially and I was not familiar with; and my generation were not familiar with installation art and video art. So this was all very new material for me. It took me a little while and I got into the swing of things, and we started buying a lot of works together. Affordable works, because these were young artists, who were trying and experimenting, and there were conversations and dialogues. But of course with the boom in 2004 and so on all of that slowed a little. I am not sure if we have ever stopped buying but everything changed.

Choreographed Culture – Danjuma Collection

Amid the melee of commotion that proliferates during the art world’s most significant calendar event, Frieze; there are other shows that more regularly would be considered critically necessary. Ceased upon they are choreographed into the autumn art curriculum as a consequence of the art fair, and serve to amplify the energy of international contemporary art. These are exhibitions that might well be lost on the cultural periphery, or serve as engaging counterpoints to the main event; for the inventiveness of artists and institutions alike. On the edge of London’s Fitzroy Square, inside a period house that appears as significant as any interlocked into the square, is an exhibition of works of the young collector Theo Danjuma. Having acquired a wealth of works that focus for the majority on the contemporary African art scene; Danjuma has audaciously drawn together a calibre of artists the like of which have been a long time coming. Among them Berlin based Vietnamese artist Danho Vo, Norwegian Matias Faldbakken, Los Angeles based artist Oscar Tuazon, British YBA veteran Sarah Lucas. European and American works that have been drawn into the Danjuma Collection alongside pieces by Nigerian Emekha Ogboh, Ethiopian born, New York based artist Julie Mehretu, South African Nicholas Hlobo; and Ghanaian born, London based artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. In a temporary exhibition of two and three dimensional works that are collectively and critically of the moment, it is impossible not to be thoroughly engaged by these virtuoso artworks. That are a measure of the graffitied styled and unpoliced actions of a new generation of international artist reaching for materials as the source of their ideas. And the verve and vigour with which the majority of the artist’s collected by Danjuma work is quite inspired.

Rooted to the basement is Matias Faldbakken Untitled work (Golf Bag) 2011, which is in close proximity to South African Dineo Seshee Bopape’s Exit 2103. A work that is comprised of three television sets and two speakers that appear to have been high-jacked by an extra-terrestrial energy transmitted on the screen. Whereby the routine of figures and television dialogue are replaced, exterminated even, by these altering landscapes of fluctuating colours that have turned these containers of entertainment into messengers for other wordly acts. Bopape’s relic televisions reflect the hyper modernity we have become accustomed to in the west, from the more cumbersome recycled objects that have become the steadfast instruments of every other home in the world.

The televised alien invasion leads one in the direction of a flurry of synthesised sounds that accompany a series of short film pieces entitled (dis)connect I,II, III, IV by Nigerian Emekha Ogboh. Which for the most part are some of the most impressive collaged film pieces to have come onto the art scene for a long time. Against this absorbing yet abrasive soundtrack from the city, these interconnected films appear as technically crafted mirror images of bold technicoloured pedestrians and motor vehicles that inter-collide into the subdivided lines of the elongated screen. And as remarkable acts of visual alchemy, the generated scenes of figures emerging in the foreground, melting into their symmetrical other half, before impressively dissolving in on themselves, becomes positively hypnotic. As these generative and progressively sequenced events become the sophisticated narrative for what would otherwise be a more original street scene in Nigeria. The disconnect series appears as a synthetic rereading of the very ordinary, as Ogboh’s interlaced patterns of architectonic shapes and human anatomy make for a thoroughly arresting work.

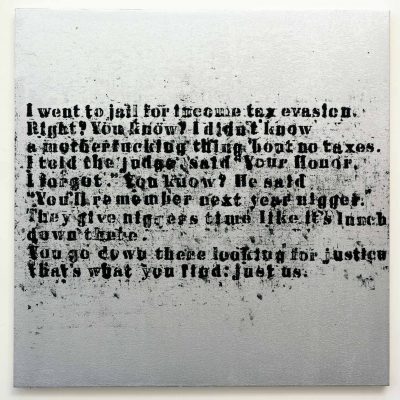

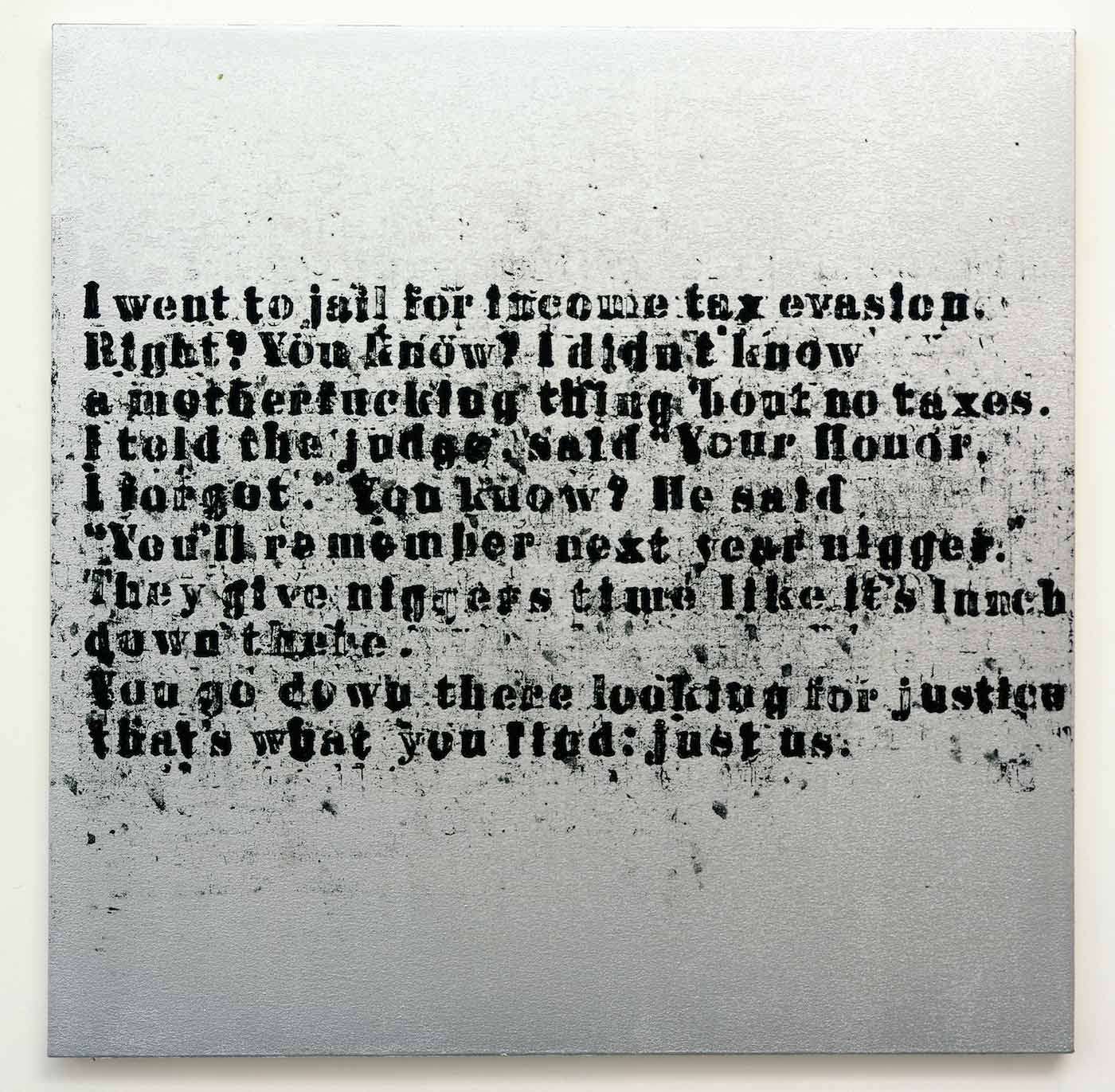

In an adjoining room in more of a domestic setting is a work by German artist Yngve Holen, beside a striking canvas by Black American artist Glenn Ligon. Whose edgy and unapologetic repertoire proves utterly of the moment. In a work that rests on the wall as untidy graffiti, Ligon’s Just Us #6, 2008 reads as a prophecy for modern times. As eloquent as anything by (Jack) Kerouac or (Allen) Ginsberg, from whom this typography appears to have been borrowed; Ligon reads the riot act on being black in America. In a disjoined and partly illegible text, as black on a silver skinned canvas, the paragraph of words reads ‘I went to jail for income tax evasion’, and goes on ‘You go down there looking for justice: that’s what you find: just us’. Ligon’s diction is remarkably dynamic, and the work appears to be a throwback to the era of American counter-culture of the 1950’s; of which Kerouac and Ginsberg were a part.

Zimbabwean Kudzanai Chiurai’s oil on canvas work White Picket 2011, is purposefully lodged into a corner of the stylish upper studio space. The work reads like a contemporary take on much of the signature style of American artist Jean-Michel Basquiat, yet with greater menace. The painting has a central figure gripping a blade in one hand and a blunt instrument in the other. The apparatus of violence that has since become synonymous with the barbarism of the prolonged civil wars across central Africa. With a charcoaled outline of a picket fence differentiating the foreground, that Chiurai’s masked protagonist occupies, from the coloured background; Chiurai’s has loosely painted in lettering that begins to explain the works canon. Of which you can initially make out the words ‘In 1865 there was nothing more dangerous’, which provides a loose narrative for the menacing interplay between symbols of brutality, and the decorative ease with which Chiurai applies colour to canvas. The artists brilliantly engendered work is placed opposite the more distinctive painterly style of London based artist Lynette Yiadom-Boakye. In which a whole cast of black characters take to the canvas’ stage, in what appears to be a more convincing version of modern history.

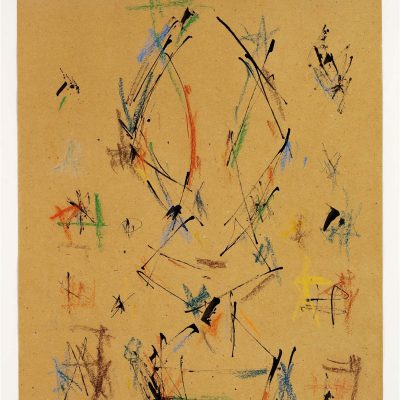

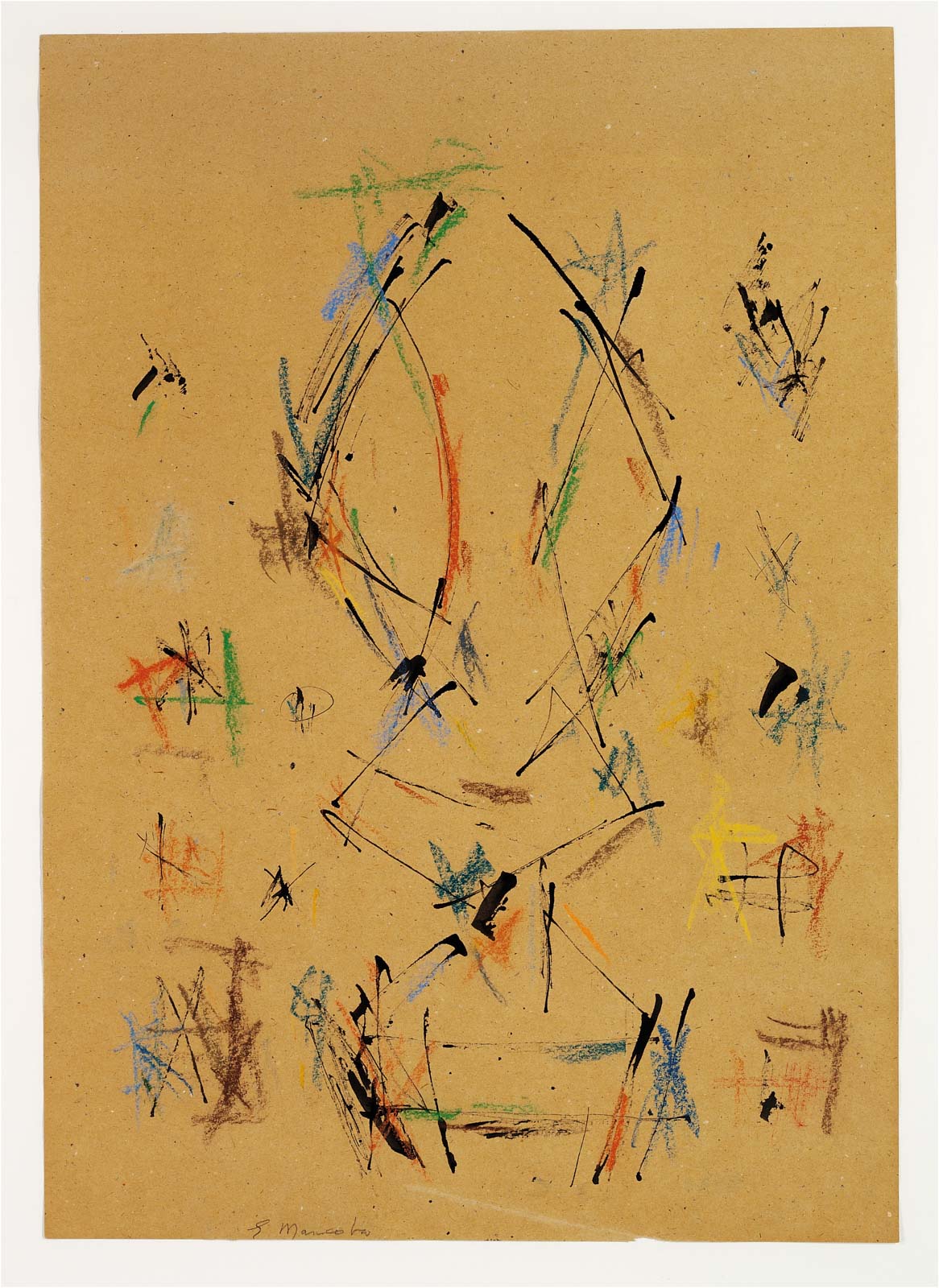

South African Ernest Mancoba’s Untitled 1989- 1990, ink and oil pastel on paper reads like a series of conformations, of ink and pastel drawing swords on a beige coloured battlefield. As Mancoba’s haphazard marks have the same intensity and energy as anything by Russian colourist Wassily Kandinsky. Here there is the minimum of commotion, as the background dominates these hurried marks that the artist comes to settle upon. The work is the measure of quite remarkable man, who was born in South Africa, moved to Paris to study at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Décoratifs. Before moving to Denmark to become a founding member of the CoBrA group. Before returning to Paris, where Mancoba eventually died in 2002.

Addis Ababa, New York based artist Julie Mehretu’s Mind Breath Drawings 2010, of which there are two works in the collection, read as remarkable graphite on paper compositional curiosities that resemble something of the ideals of early Italian Futurism gone awry. Much looser in trajectory and tone, Ababa appears to allow her mind to determine the direction of travel. And as acts of the unconscious these carpets of tangled marks appear as the register for the almost schizophrenic mind of the artist, as she challenges the condition of existing in a city. And as a consequence Ababa’s unfathomable marks read like the unguarded collision of industries of people climbing over another to penetrate the institutions they serve. For Ababa the evidential fallout becomes the “story maps of no location”.

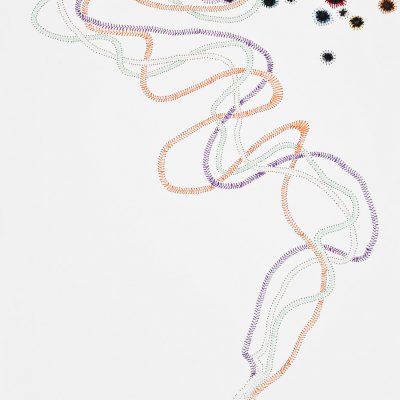

On the first floor South Africa Nicholas Hlobo’s work Amaqabaza 2012, and a second Condoba Upsheka 2012, with a third work Izichenene 2012, not on display, resemble the unidentified moving organisms that settle inside the eyelid. Hlobo applies a combination of ribbon, watercolours, and aluminum to a neutrally coloured canvas, in a haphazardly decorative attempt to create something otherworldly. That in the less coloured Izichenene appears like the trail pattern of a cumbersome microsopic creature. Applying bullet holes into the canvas from top to bottom, Hlobo threads coloured ribbon into and over the canvas, in order to create these disseminating patterns that climb up like unraveled intestine. In Amaqabaza Hlobo appears to have shaped the organic proliferation of forms with a looser combination of colours and residual tea stains, and the decorative combinations make for a series of intensely beautiful work.

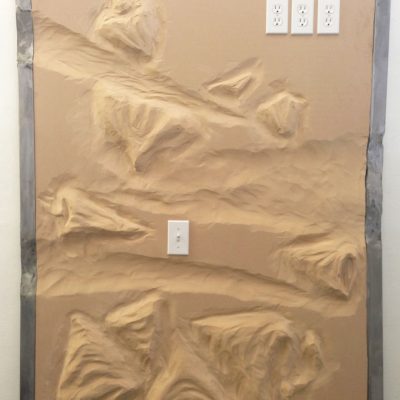

Alongside works by French Algerian Neil Beloufa’s work Sad Strawberries 2013, from the vintage series, that read like fashionable panelling for a newly designed interior. With these incongruous domestic switch and sockets applied to a steel framed MDF board that has been pummeled with a heavy duty grinder. To create these undulating gradations that appear more sand dunes than sand coloured board. And any attempt to understand this work upon closer inspection is unrewarded. Blowing 2013 is another work that is socketed up, with a wire leading to the floor, as if the induced energy that might illuminate its register somewhat further.

With the unexhibited synthetics of Spaceship Door 2012, for which Beloufa has stretched printed vinyl over steel with bolts; Beloufa’s preoccupation with materiality demonstrates the artists accomplished ability for juxtaposing material over matter. Rooting through this elegant house top to toe, Theo Danjuma’s collection confirms the spirit of a new kind of contemporary compositional art from all corners of the earth; that makes for a more inclusive display of works.

Technocrat – Eric Schockmel interview

Attending the Ecole de Recherche Graphique in Brussels in 2002, before moving to London in 2006 to read an MA in Communication Design at Central Saint Martins. Adopting the city as his own, Eric Schockmel initially exhibited between London and Luxembourg. Thereafter developing an incredibly sophisticated platform for his animated artworks internationally. With his technological masterpieces at the cusp of the creative industries, science and technology, Schockmel’s work recalls something of the collaborative ideals of 1967 group Experiments in Art and Technology, which included Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman. As his animated entities appear as equalled measured as music videos, multi-screen installations, high-tech commercials and wannabe video games. Describing “motion graphics as an opportunity for storytelling”, Schockmel is interested in the collaborative qualities of working with other designers, animators, scientists and software developers, and the potential of sampling sound, in order he can arrive at something original.

Conscious of the spread of new technologies upon the lives of the individual, Schockmel’s advanced visual prophecies come as a consequence of a culture of excess. Whereby our want of American science fiction and Gucci-can only be temporarily unbalanced by an online assassination attempt in Nigeria; that comes from a proliferating war in the Middle East. And this kind of variable intensity of remote experience, by which we are entertained as much by staged comedy as we are by the relentless sound of gunfire; suggests something of a new kind of ungovernable reality. And such variable circumstances become the platform from which Schockmel’s work appears to address our greater subservience for a more mechanised experience. Which have us exchanging reality for make-belief and vice-versa. As Schockmel explains something of the fallout of believing entirely in the future; “the animations, are dealing with the possible outcome of technology we are using and developing. And most of these consequences are probably unanticipated at this point.”

Currently exhibiting at the Casino-Forum d’Art Contemporain, Luxembourg, with a jarring juxtaposition of carefully crafted projections set against concrete. Schockmel’s animated sequences are sited in the underbelly of the gallery, where Macrostructure’s light deprived graphics glow with a technological charge that proves almost mesmerising. From within the basement of the gallery, in which walls and pillars fashion a bunker styled space, Schockmel’s individual films read like commercials for future technologies, in which all human presence is jettisoned entirely. And tellingly when discussing the installation, what becomes interesting for Schockmel, was the opportunity to introduce a number of works in close proximity to one another. Allowing for sound spill, and as the artist intended, for an accumulative aura to penetrate the audience’s sub-conscious, in order that they are positively disturbed by the machinery of the works.

Schockmel explains how his work profited from the very elemental spaces. Suggesting “what is really interesting about the Casino is that down here we have a very industrial structure, and we have very interesting conditions for sound; because the sound between these rooms, and the (projected) machines overlap.”

Works of significance include The Shrine 2014, which is elegantly esoteric in appearance. Emerging from the tonal darkness like a biblical landscape, where upon technology delivers its vision. The Shrine which is part of the What If You Created Artificial Life And it Started Worshipping You series, with its emotive sound track and idyllic natural rhythms appears to pay homage to the tranquillity of an alternative dreamlike setting. In which the animated wildlife, the rippling turn of translucent water unsettled by a rolling waterfall, the Japanese styled carpeted islands and protruding rocks, are all backdrop to a series of illuminated lanterns that twist and turn on their elevated axis, like alien figures looking to mate. Resembling something of John Wyndham’s mobile triffid plants, the more intriguing these elongated nucleuses appear as they hover over the serene landscape, the more encompassing their appeal. Schockmel’s earth coloured palette and the depth with which he manages to extend the landscape out across the screen, makes for a remarkable piece of story-telling. In which the constructed world becomes entirely plausible by the time it arrives at its closing sequence.

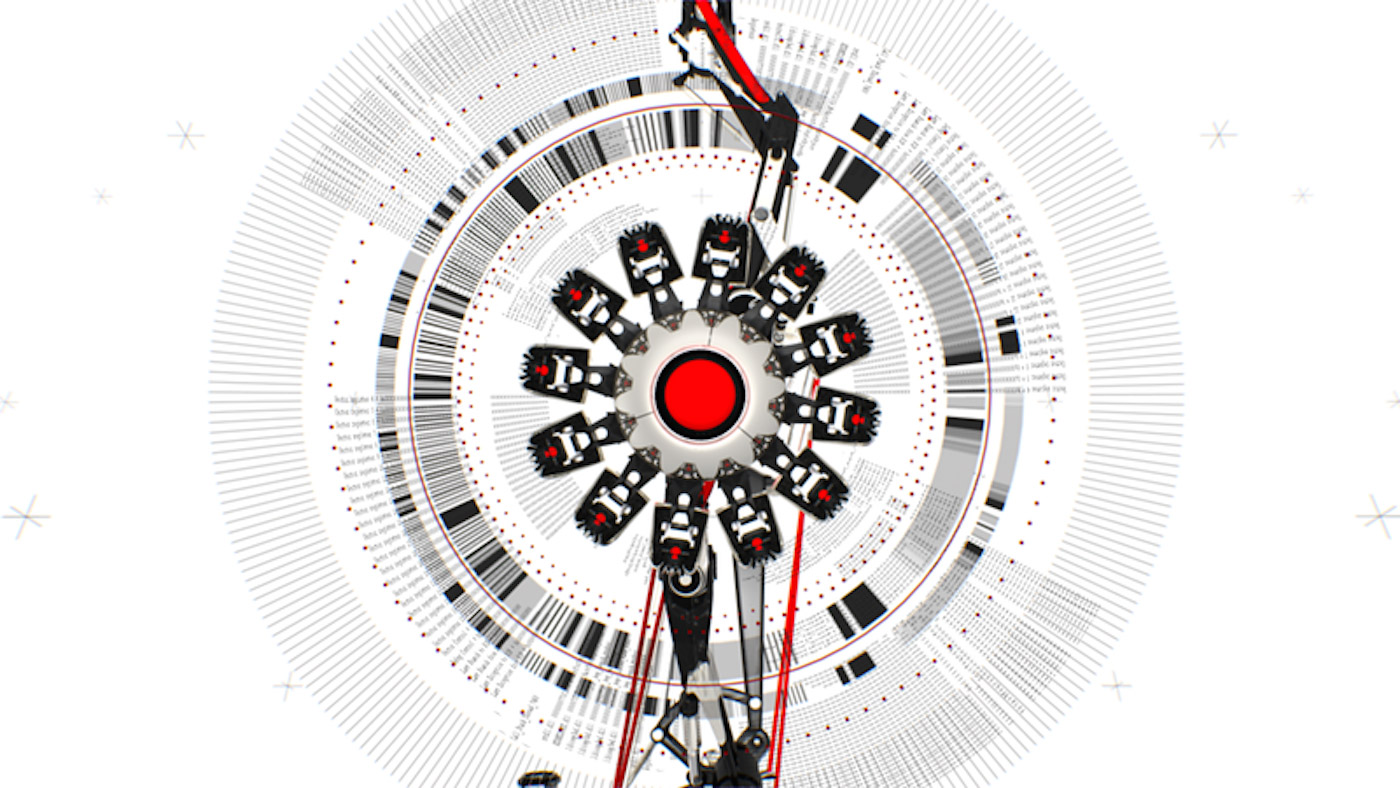

Feathered Serpent 2014 is another part of the What If You Created Artificial Life And It Started Worshipping You series, which appears as a sophisticated take on an alternative life source. Entirely forensic in appearance, set against a skin of brilliant white, cushioned by the rhythmic hum of a technological heartbeat; Schockmel’s animated entity reads like the closing moments of a new science fiction film. In which the anatomical arm elevates this precise symmetrical hub of automated petals that collectively protract, revealing a penetrating eye. All of which is elegantly encircled by a series of rotational rings that resemble Saturn’s planetary system in orbit. Spreading out to touch the edges of the screen, these dot and dash circles run in opposition to one another like helicopter blades, as they effectively animate the central axis. Giving the encircled merry-go-round an arresting appeal. And as the central narrative, when a precise number of rotations are complete the outer rings disappear from view as proficiently and very effectively as they originally appeared. In order the automated arm can draw the central hub back in on itself and balance is restored.

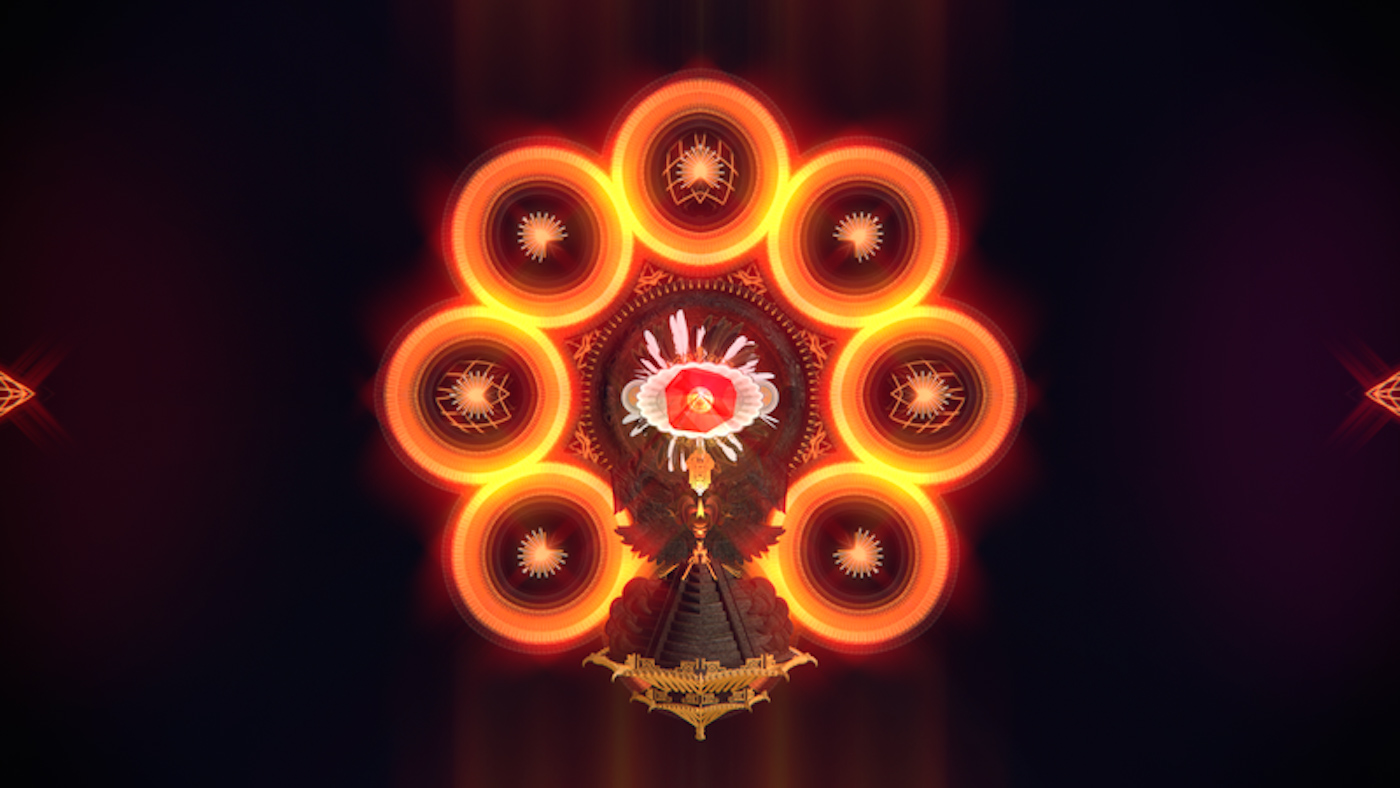

Equally spell-binding is The Vision 2014, for its animated complexity. Resembling the rotational charm of a child’s kaleidoscope tube, in which the patterns positively expand and rotate beyond all recognition. Schockmel’s work is centred by an ornate alter piece from which everything else emerges. At its tip is a revolving ruby coloured stone that turns in its axis, in front of a cushion of bird features. And at its base are a series of steps that leads to an eternal flame, from where the works generative energy appears to come.

As the tonal vibrations of sound resonate like distress signals, so the atmosphere metamorphoses into an impenetrable layer, from within which a crystallised collection of circles emerge from behind this central deity. The warmth of which is all-encompassing. Equally the complexity of these expanding circles and the mirrored patterns that are generated in this work, are as attractive as they are inspired. And it becomes almost impossible to qualify from where one circle of shapes begins and another ends; as these highly stylised tessellations indulge upon one another like an orgy of animated beauty.

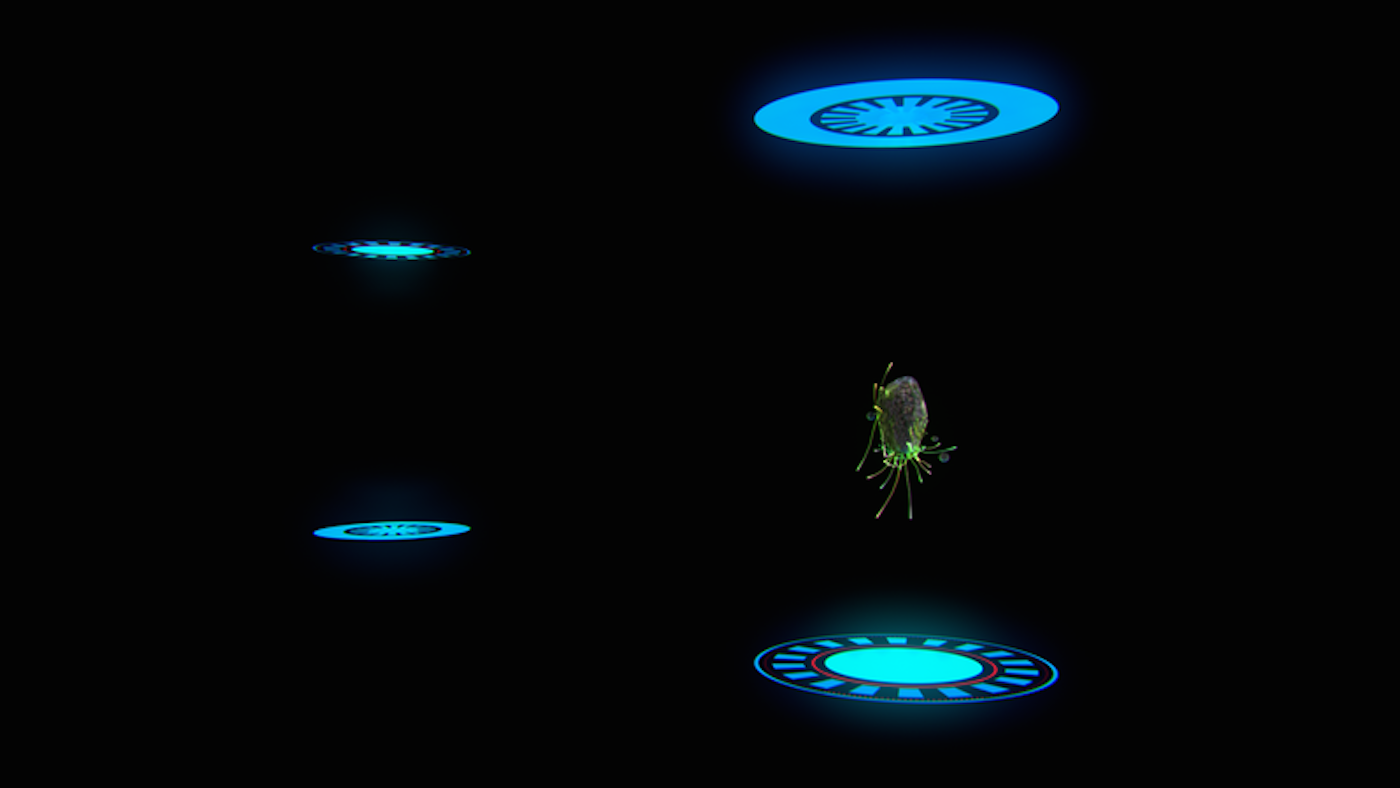

Darker Lost Holon In A Portal Loop 2014 is a work that generates a certain level of unease, as these mutant incarnations appear to drop from one illuminated portal into another. Set against a dense layer of black, it becomes impossible to reference anything of the world outside, artificial or otherwise. Thus what centres your imagination are these episodes of animation, in which a blue sphere of light appears and disappears, creating a point of entry and beneath it a point of exist, into and out of this transitory space. That has the audience transfixed for a moment. Deliberating over whether these clandestine creatures are falling into or out of a lesser predicament. The slick technological edge of this work comes with Schockmel’s signature use of an automated soundtrack that suggests that what might appear as one-dimensional, is fact a work of incredible depth and tonal atmosphere. The repetitive sequence of one mutation falling into this sliver of space and out of it, followed by another; returning between the two, becomes almost hypnotic. As the illusion of unqualified space and unfathomable depth serves to illustrate just how well Schockmel creates these futuristic animations. Works that we as spectators are as much attached to, as we are detached from.

Eric Schockmel’s three dimensional works for the What If You Created Artificial Life And It Started Worshipping You, shown at Casino Luxembourg appear as detailed universes in which he creates enclaves of animation that lead to these technical but very tender sequences. Life-affirming in their atmospheric tension, Schockmel’s short animations serve to demonstrate that he seeks to address a whole series of very complex and equally compelling ideas via the compass of animation. Not least the technological singularity’s effect from artificial intelligence, first discussed by Historian Henry Adams in the early 1990’s. The controversial advances of bioethics, and the sustained interest for primal worship; addressing the balance between man and nature. Delivering art as science fiction Schockmel’s work appears to demonstrate that there is a central life source at the root of everything. And that however sophisticated such mechanised scenarios become, that there is an elemental energy that furnishes all life. Significantly Schockmel’s video-game aesthetic references a future in which technology can potentially become sophisticated enough to allow for the birth of automated organisms, that themselves evolve the sentience of their own self-awareness, and subsequently start to worship their creators. Schockmel’s visionary work takes us on a profound journey that is as technologically trusting as it is aesthetically attractive.

Major festival participation includes transmediale.09, Deep North, Berlin (2009), VIMEO Festival, New York, (2010), onedotzeo_adventures in motion festival, BFI Southbank, London, (2011), Ars Electronia Animation Festival, Ars Electronica Linz, AT, (2012), The British Animation Film Festival, London (2014), FILE ANIMA+, Sao Paulo, (2014); and exhibitions include, Japan Media Arts Exhibition, National Arts Centre, Tokyo (2009), REMASTERED: An Intel Visibly Smart Production, London/Manchester (2011), Fail, Galerie Nosbaum Reding, Luxemburg, (2011). I’ve dreamt about, MUDAM, Luxembourg, (2014), VESTIBULE, Bergman Berglind Contemporary, Luxembourg, and MACROSTRUCTURE, Casino- Forum d’Art Contemporain, Luxembourg. (2014), FILE Media Art Exhibition, Galeria de Arte do Sesi, Sao Paulo, (2014).

Arrangement of Skin – Polly Morgan interview

With childhood ambitions to act; Polly Morgan, born and bought up in the Cotswolds; completed school and studiously decided to attend Queen Mary’s, University of London instead. Pedestrianly graduating in 2002 with an English Literature degree. It was her extra curricula activities, including working at the Shoreditch Electrical Stores, London; that proved significant for her foray into the art world. A popular bar for artists and graduates alike, it was where she met her then boyfriend, British Sculptor Paul Fryer and started to attend East End openings. Influenced by Fryer, and the bar’s clientele quite possibly, Morgan took up ink drawing and clay sculptor, whilst attempting to decorate their apartment above the bar. Experimenting with mediums, she finally took an interest in taxidermy; as a consequence of attempting to buy ornamental creatures, and being frustrated by how alive the encased animals looked; wanting them to play dead. It was suggested to her she learn the technique herself, and she subsequently contacted the most qualified taxidermist in the country, George Jamieson, of Cramond, Edinburgh. With who she learned, within less than a few hours, the initial practice of stuffing a dead animal with a frozen pigeon.

An almost revelatory experience for the literature graduate, Morgan immediately took to taxidermy as a preoccupation for her engrained love of nature and its regenerative energies. Hastily (as she describes it), producing four works in those first few months, that for their daring caught the eye of the celebrated British graffiti artist Banksy. Morgan had by then determined her own artistic enterprise; that would draw this self-taught artist to the attention of collectors Anita Zabludowicz, and David Roberts. And gallerists Jay Jopling and Mollie Dent-Brocklehurst among them. Banksy invited her to exhibit at his temporary gallery, Santa’s Ghetto, and from there she exhibited at White Cube, London (2008), the Haunch of Venison, Burlington Gardens, London (2009), Gimpel Fils, London (2010), Kunstmuseum Thurgau, Switzerland (2010), and the ACC Galerie, Weimar, Germany (2013), among others. With a solo show about to open in New York, at Other Criteria, 11 September – 22 October 2014.

Rajesh Punj: Can you possibly begin in the moment, and explain your work now and your forth-coming solo show in New York?

Polly Morgan: The last couple of years I haven’t really been particularly happy with anything I have been making. I have been struggling to enjoy it. Not ‘enjoy it’. I do enjoy it. I enjoy the making, but the process of coming up with something that I felt was satisfactory, has been quite tricky, for the last few years. And I have finally pinned it down, or pinpointed that maybe my aesthetics have changed really, over the years as I have grown older.

And also as my knowledge of historical and contemporary art has improved. Because it was terrible to start with. I didn’t go to art college. I just started making work, incredibly naiively really.

RP: Can you explain a little of your background?

PM: I read English Literature at college, not that I was especially driven by that; but although I did for a while think I would write, and I did do a little bit of freelance journalism. It just didn’t occur to me that I could do art, for some reason. I used to make things constantly, and I was really into the subject at school. (At the time) I didn’t know any artists, I didn’t know anyone at art college. It was just never suggested to me, and English seemed like the inevitable thing to do. So in a way that really helped me to start with (making work), because I was naïve enough not to question every little thing that I did. And also I didn’t have these high hopes or ambitions to be an artist. I just started making stuff. And I was living in East London, and had friends who were on the periphery of the art world, or some of them were quite successful artists. And it got seen by the right people, and picked up quite quickly. And that all snowballed the interest in it, and I felt like I have been catch up for years really. Trying to make works that justified the attention I was getting, and never really feeling I was.

RP: Art writers and critics can be a little over jealous on occasion, labelling and categorising everything pretty quickly. Leaving the artist unassailably attached to one camp or another. Is that what happened to you then?

PM: I think that’s probably what happened. And I think it was partly that I put some work in a show that he (Banksy), used to put on at Christmas. I would say yes to a show, if someone would offer me a show, and I didn’t think about the repercussions, or any idea. And I really didn’t think it would last longer than two or three years, so I did whatever happened. And it was only in hindsight that I realised that that set me off in a direction that I possibly didn’t want to go in. Anyway for the first time, these works that I am making are devoid of narrative, and they are much more about the animal as a sculptural form; as a kind of… I have chosen snakes because they are long thin tubes really, and they are malleable and you can do so much with them. And I am trying to get away from the symbolism behind snakes, which is irrelevant to the works I am making. And they are kind of modernist in influence. With these loops and curves sitting on these blocks of marble or granite, and hard wood.

RP: So this appears to be a major departure for you, from your original idea of animals encased and almost macabre in appearance?

PM: it’s a sort of bridge I think, because it’s still taxidermy. But it feels like it is taking me away from the associations of the gothic, which I always had attached to my work. Which I can understand, but at the same time I think a lot of it came from my working with material that happened to be a dead animal. But someone who draws in charcoal, their material is brunt wood, but you don’t think of it in the same way. For me it really was a material I was using as opposed to… death had to happen in order for me to use the skin, but it wasn’t about death. (Referring to her new works for her forth-coming New York show), so they are not meant to look natural in any way, they are just coiled up in positions I found attractive really. There are about thirteen of them downstairs, (in my studio), none of them actually fixed on yet. And nine of them are going out to New York.

RP: So there is a sense that these works are moving more towards abstraction of the ‘form in space’. Is that an important departure for you?

PM: It is yes; and they are works that I just like more, and they are in keeping with my aesthetic. I suddenly realised that there was this quite big chasm between the work that I was making, and the work that I like. And I would have conversations with friends about it, and they would say it’s not really relevant whether you like your own work. You make what you make and that’s what you do. You continue along that path. And I have heard that from quite a few people. And I was going along with it a little bit, but at the same time I was convinced it can’t be right to work all day, and sleep at night and think that you are producing ‘bad’ work that is pointless, and that you are embarrassed standing next to it at your own private view. Which didn’t feel right. So I think for me, certainly with these snakes, I have found a way to make something I would like to own. And get away from people telling stories about my work that weren’t in my head when I made it.

I don’t like to be didactic about the work, and suggest that this is what it means, and this is what you will take away from it. I do like the idea that it exists outside of you once you have made it, and it has its own life, because everyone looks at it very differently. I did feel that there was a real disconnect between what I saw myself and what I was making; and how other people were receiving it.

RP: How do you feel about terms like ‘decorative’ or ‘attractive’ in association with your early works?And are you consciously attempting to move away from that now?

PM: Yes quite ambivalent I suppose (about such descriptions); that is something that has always worried me about my work. To start with it was very ornamental. And actually I think it was fine, and it was okay to be doing that, but suddenly I found myself as an artist, showing in art galleries, and it was not really what I intended. And that’s when I become incredibly critical of my own work.

If I had seen my own work in a gift shop, or even in someone’s house, I would have thought ‘that is really pretty’. But soon as it was in a gallery, I would look at it as a viewer in a gallery, and think that’s not really good enough. And I think my problem is that I always try to pre-empt criticism before it happens.

RP: I interviewed (British Sculptor) Richard Wilson some months ago now, and he and I were talking about another artist who has done just that. Of negotiating their way out of control. And someone who is now clearly producing far too many works for a gallerist demanding that of them. There is a danger of submitting to that kind of prescribed pressure, whereby that is the ‘deal’, and that is what you go with.

PM: I realise I just want to enjoy my job, that’s the thing. And when it is on my terms and I can take it at my pace, I really love what I am doing. But as soon as I am working with someone who wants to work at a slightly different pace to me, I can really feel myself resisting it with every fibre of my being. And I really don’t enjoy it, and the work is no longer pleasurable, and I don’t sleep aswell. And my ideas aren’t as good. And I have learned now.