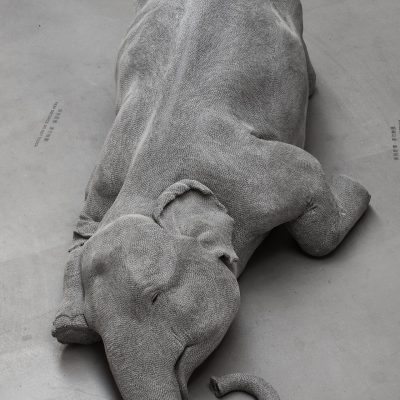

Bharti Kher has become one of the leading female protagonists of a new generation of artists holding their own in India today. Having broken onto the international art scene with her work The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own 2006, that comprises of a life size fibreglass elephant recoiling on the floor, covered from head to toe in silver bindi’s; Kher has since established herself as one of a handful of artists at the cusp of the contemporary art scene. Shifting from the UK to New Delhi in the early nineties, Kher had to assimilate to her surroundings, while still managing to retain her own independence. And like so many of her early works that are born of a plethora of discarded materials; the elephant was influenced by a faded photograph of a collapsed elephant being manhandled and manoeuvred into an awaiting truck. The tragic imposition upon this allying mammal was perceived by Kher to be “an artwork in the making”. And as a work of immense beauty it proved to be a sensation among the international art collective. Impulsively acquired by philanthropist and collector Frank Cohen for his Wolverhampton collection, which is included in a Manchester City Art Gallery show in 2010, aptly entitled Looking East in which Cohen opened up a very small part of his collection to the public.

Bharti Kher was also included in Saatchi Gallery’s Empire Strikes Back exhibition, 2010. A survey show of contemporary Indian art, which included The Nemesis of Nations 2008, which is a work that has become as synonymous with Kher’s practice, as the vinyl floor works are regarded as British artist Jim Lambie signature style. Multi-layered and multi-coloured, these circles of felt are concentrated onto gallery walls and canvas as many as possible. For Kher their cultural significance is central to her art practice. A reoccurring motif, likened to the wheel rooted to the centre of the Indian flag, the bindi is at the centre of all social and cultural identity in India, and a sign of the marital woman and her place in society. Kher explains “The bindi has become many things now after using it for so long, a marker of time. It functions as both a material that transforms the surface of a work like text or codes and reinvents the clarity of a ritual that signifies that you open your eye and see. The visual aesthetic is really not something I can ignore and yes it’s one of my signatures.” For that reason Kher’s repeated bindis, the distorted layering and over-layering of the original form, disorientates and destabilises the motif, one among many. Corrupting the essential beauty of the bindi with this work, Kher goes some way to suggest symbolism is constantly subject to social change and she positively challenges the role of the woman in a continent stifled by tradition.

As an artist Kher is more interested in the intrinsic processes that are inherent in making her works, and demonstrates a laudable modesty that encourages her to derail any talk of her being ‘more important’ or a ‘leading artist’ among her contemporaries.

With works like Hungry Dogs Eat Dirty Pudding 2004 we are reminded of Swiss artist Méret Oppenheim and her early Dada and Surrealist interests. Hugely influential to her contemporaries in and outside of the surrealist movement in the 1920’s, Oppenheim was a leading female artist whose works consisted of everyday objects arranged as such that they alluded to female sexuality and feminine exploration by the opposite sex. For Kher such associations are rudimentary, “In the tea sets series her (Oppenheim’s) hair covered tea cups bore the same strange fruits of the tea ceremony that I wanted to explore. Meetings and encounters that are somehow neutralised in a ritual handed down over centuries to talk and share. My piece took the twist like Oppenheim’s but in my own way.”

Another work of considerable merit is The Absence of Assignable Cause from 2007 in which Kher has recreated a disembodied whale’s heart in fibreglass and decorated the enormous heart and protruding artilleries with different coloured bindi’s. A speculative work again based on images, this time from maritime journals and obscure articles that have been surmised to produce this monumental work. And Kher appears to have indulged in this instance in a fleeting interest in the wonder of a mammal’s heart as a metaphor for something else entirely. As with The Skin Speaks a Language Not Its Own 2006, it is the scale of the work that delivers such a spectacle. Intentionally intrusive upon the space whilst still retaining something of the intimacy of a living organ.

Bharti Kher has since exhibited at her Swiss gallerists’ London and New York spaces, and it is no coincidence that her husband Subodh Gupta’s gallerist, Hauser&Wirth is one and the same. Far from being overshadowed by Gupta’s success, Kher has carved out a position all her own, that merits as much attention. While Gupta indulges in the monumental, Bharti Kher is an artist committed to exploring cultural misunderstandings and social codes, using the breadth and depth of contemporary art practice to arrive at these misshapen objects and installations. Highly regarded for her sculptural works, Kher has also produced paintings and sculptures that purposefully challenge some of the cultural and social taboos intrinsic to the class systems in India.

Likening herself to the well intentioned ethnographer pouring over the machinery of her culture, Kher delivers a very forceful reinterpretation of modern India that shallows everything up in sight, much like a typhoon, and throws its back at us in such unfathomable reconfigurations. Human limbs attached to animal parts, objects upturned and disassembled, colours appearing like diseases. What motivates Kher, with her ability to achieve almost anything, goes back to her original intention for ‘intimacy’ and ‘simplicity’ in her work. Ideas she originally grappled with at art school in Newcastle. “I think I go backwards and forwards all the time. Most of my work refers to other pieces I have made because your concerns stay essentially the same whether they are naive or considered.”

Reluctant to eulogise the painters and sculptors who have influenced her work, Kher is more democratic in her praise for the anatomy of her adopted city as a greater influence. “I look everywhere and copy everyone like a magpie who takes what it needs, turns an old shiny button into a beacon. Most of us are products of our lives.” Therefore like her contemporary Jitish Kallat, art is a by-product of life. Where Kher borrows and rewards herself from the inventive sub-cultures that exist side by side in a country tittering somewhere between self-sufficient harmony and hazardous chaos.

Domestic hoovers covered in garish animal skins and trees bearing the fruit of small unidentifiable creatures. These are the kind of unusual morphing’s that Bharti Kher has made her own and in discussion it appears that she is influenced as much by the geometry of (Piet) Mondrian as she is by the machinery of domestic appliances. Allowing her to beg, borrow and steal as much from the grit and mortar of the underbelly of the city, as the more established cultures narratives of contemporary art. For all of that Kher confesses to “never underestimating the power of a great piece of art”. Given to elaborating upon the significance of art history on her practice, Kher professes to an appreciation for the universality of the whole experience in one go, “If I can see Malevich I don’t have to be Russian Supremacist avant garde or you don’t have to be Dutch to love Mondrian” “At art college I looked at Francis Bacon, Francisco Goya, Diego Velasquez, 15th century Dutch painting, I looked at tons of books and art magazines. I was schooled in the UK so I didn’t study Indian history of art. You fill in those gaps now on your own”.

Such motives for new works appears to suggest that art for her generation of artist is sought and struggled over in the everyday; positioned somewhere between a fabricator and jeweller’s, across from a type factory and a paint store. A far cry from the utter isolation one might associate with Pablo Picasso painting Guernica in Paris in 1937, or Jackson Pollock pouring paint for Number 1, Lavender Mist, 1950 from his outdoor studio outside New York. This insatiable ‘appetite for the everyday’ appears to have torn apart the divisions for creating art entirely from ones studio, as American Mark Rothko might have done, and what is significant now with contemporary art practice, is what appears closer to the appraisal of modern culture eulogised by Rothko’s contemporary Andy Warhol. Where everything and anything goes.

Obviously such actions and influences were the foundation for modern art history, from the chaotic misadventure of Dadaism in Europe at the turn of the century, to the brash confidence of American abstract expressionism; art has always been a reaction to an established culture. Reading over Kher original interview correspondence, it appears her inscrutable appetite for new ideas is as a consequence of her manufacturing beauty from the detritus outside her studio. In her “feelings for being from neither here or there”, Kher regards herself as much Indian, as she is British. And her international position reflects her broader narratives.

When discussing the originality of her work Kher is quite adamant of her artistic autonomy, “It doesn’t bother me if people think it’s been done before… authenticity is not something I adhere to.

You have to see where and why the work is coming from where it does”. And again Kher’s contemporary Jitish Kallat describes “the city as his university”. A looking glass through which he freely borrows from everything as a modern day flâneur reaping his reward. Thus as a consensus contemporary works are generated in and amongst us; equally by artists and city dwellers alike. And as with Marcel Duchamp and Andy Warhol before them, an idea or an entire work becomes art when it is reappropriated from the city into the incubated isolation of the gallery space. The fuel for such wondrous works is aplenty then in a city that thrives on the energies of such a diverse populous and on the infrastructure of a by-gone age, in which Kher has profited from her use of almost anything that comes into her studio.

In context Kher is of a generation that appears at the vanguard of a new look India, all of whom have successfully infiltrated these shores with such ambition that Saatchi’s aptly titled exhibition of contemporary Indian works, The Empire Strikes Back shows something of the profitable exuberance that make for exciting times for this spirited group of Indian artists. As a swelling reception for contemporary Indian culture appears to have fashioned a zeitgeist that has rewarded European and Indian dealers and gallerists alike. Kher explains “any interest is great for people here who incidentally have been practising for as long as anyone else, anywhere else. Parallel movements and cultures are open to any who wishes to involve themselves.” Kher is an artist at ease with herself, against a background of new technologies, the allure of Bollywood, and a political system curtailed by bureaucracy, she is shaping a new narrative for new audiences.

For her much anticipated London and New York shows Kher managed to successfully translate some of those new ideas to a larger audience like no other. Juxtaposing scale and decoration with tantalising visually absurdities, Kher appears driven to create difficult and aesthetically involving works time and again. And the cultural slippage, not belonging to either India or Britain, allows her the outsider role, as she observes reality and borrows from it tenfold. Delivering works that illuminate with an aura that radiates around the work like Donald Judd might once have done. Kher’s invented narrative becomes the precise point of departure for her artworks, as she appears to be constantly acting and reacting to the cultural connotations that all of these objects, materials, and symbols provide. Acting to intentionally strip them of their context, in order they can become the bricks and mortar for a new artwork.