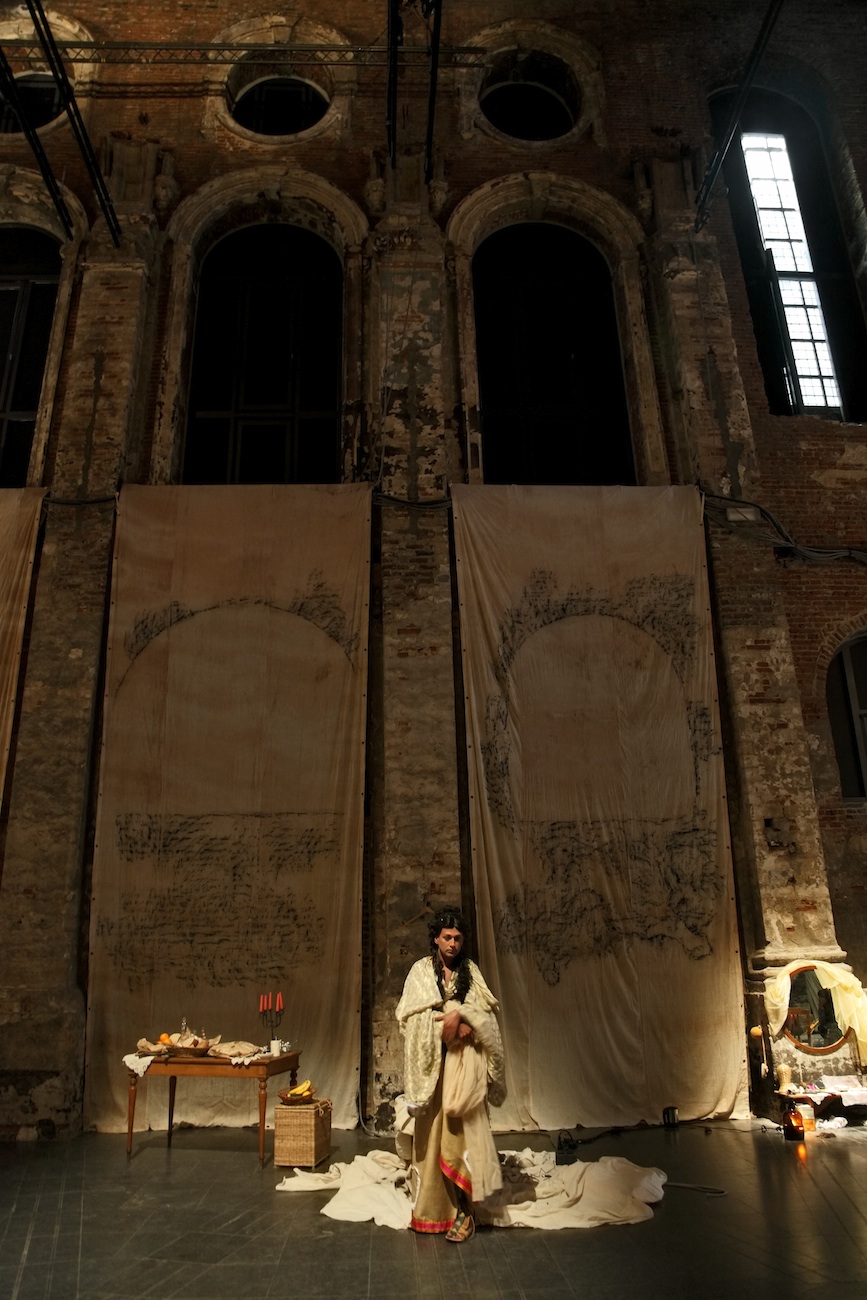

There is a glorious admiration one has for the performative work of Mumbai artist, Nikhil Chopra, whom without pretence or profit, has single-handedly propelled himself onto the international art scene, with a series of acts that might at first appear as preposterous as they are profound. Likened to a seasoned actor going on stage, Chopra painstakingly decorates himself in regal make-up and pompous costume and then without too much deliberation enters into another world in which his audience no longer have the privilege to talk to him; becoming spectators falling away into a theatrical semi-circle. During his performances Nikhil Chopra has the endearing ability to get into character for several hours at a time, days even, and then return from the brink to wash and undress and talk very easily of his need for a cold beer and a particular dish of food. Chopra himself confesses to living well and indulging at every opportunity, for one who suffers for his art there has to be some reward. But in no way arrogant, Nikhil Chopra has an unabounding humility about him, whereby he admirably furnishes our conversation with a distinct lack of ego. When quizzed about his involvement in the 2011 Centre Pompidou show, Paris, Delhi, Bombay, (curated by director Alain Seban), Chopra saw the exhibition as being as much a new opportunity as it proved a straitjacket. Drawing on the same leading contemporary artists, ‘Subodh Gupta’, ‘Bharti Kher’, ‘Ravinder Reddy’, ‘Nalini Malani’, ‘Riyas Komu’ among them, Chopra was invited to exhibit side-by-side, in a slightly amateurish appraisal of contemporary Indian art. And within such contrived cultural circumstances Chopra never saw his work as any more significant to the stylish painterly works of Thukral and Tagra, or the appropriated ready-mades of Bharti Kher.

If the duration of his performances are anything to go by, then he outdoes his contemporaries for the sheer extent to which he willingly labours for his art. In conversation I argue that whilst the majority of his contemporaries in principle make more conventional works, ‘paintings’, and ‘sculptures’ that are constituted of ‘ready-made objects’, he himself choreographs entire sequences of related events that have him dress and undress whilst physically drawing in charcoal vast surrounding landscapes for posterity; all the while working without dialogue or the presence of accompanying characters. For Chopra that is what he does, as it is what they do, and he doesn’t wish to engage in a conversation about aesthetic hierarchies. But it is impossible not to acknowledge the remarkable journey Chopra has made, from his tentative beginnings in Mumbai, to draw performance and performative art back into the mainstream, and firmly back onto the cultural map.

Historically whilst in Europe and America, performance art has always been a significant part of modern and contemporary art practice, with the anti-art strategies of European ‘neo-Dadaism’, and ‘Surrealism’ in the 1920’s and 1930’s, when artists initially took to the stage, intentionally dressing in idiotic costume and reciting anarchic poetry, were collectively interested in unsettling or subverting a modern understanding of reality and modern aesthetics, post first world war. Decades later that initial wish for a subversive avant-garde, led historically to the more sophisticated notion of ‘the happening’ and the associated term of ‘art intervention’, whereby artists sought to democratise art and make very subtle changes to an existing situation or circumstance, as an artistic act of intervention, without willingly telling an ‘unsuspecting’ audience of what was happening, and of where the artwork was.

So the work itself, if anything was as much about the process of it coming about, as it was about the intention of the artist. (British artist Cornelia Parker wrapped French sculptor Augustine Rodin’s (1886) The Kiss in a mile of string, as homage to Dadaist Marcel Duchamp), And then there were those artists engaging very directly with notions of ‘a happening’ or ‘performance art’ in the 1960’s and 1970’s, who were eager to develop new approaches to their own practices that were related to something more immediate, and within ‘real time’. (French artist Yves Klein, famously doctored an image of himself leaping from a window onto a dishevelled street outside, in October 1960. Not an action as such, it was Klein’s statement of intent, of what was to follow and Americans Yoko Ono, Carolee Schneeman and Joseph Beuys, all developed their own understanding of where performance should go, as a vehicle for engaging with an audience in real-time.)

And such circumstances were a major influence on what Nikhil Chopra saw as the opportunity for him to loosen up his aesthetic interests, and to engage more directly with wider ideas of performance and theatre. Yet for Chopra based in Mumbai, of a traditional schooling, the act of engaging with an audience more directly was something that was not readily recognised in India. As performance is still associated with notions of cultural theatre and traditional dance. The majority of which is related to religious fables.

It could well be argued that besides a greater desire for a more multi-disciplinary approach to contemporary art making, that artists like Chopra were interested in pursuing, that the concurrent inflated interest in the Indian art market internationally, (with the rise of artists like ‘Subodh Gupta’, (New Delhi), ‘Jitish Kallat’, (Mumbai), and ‘Bharti Kher’ (New Delhi), among others), bought about a premature shift, that had a new generation of artists reacting to the ‘commodification’ of art, by taking the lead and replacing ‘objects’ with ‘actions’, and very significantly seeking to re-democratise art, in order in its purest sense it could become about the choreographed moment.

As the event itself becomes a currency that replaces the rudimentary mechanics of object-making becoming profit-making, and very significantly mirroring what had happened in America in the 1950’s and 1960’s.

As an experience Chopra’s audiences are subject to a lesson in morality, as he has eloquently described how ‘it is important to be this sadistic gentleman, to rub him into the ground, bring him to his knees, in a sense to consciously enter into this duality, to play master and servant, to be part of the past and of the present, hero and valiant, to play maharajah and coal-miner, to play a grandfather and son. To be naked and dressed up. This duality, the opposite poles in my performances is what interests me immensely, as I take the audience from highs to lows at any given time.’ And the ‘unqualified experience’, or ‘happening’ as American Allan Kaprow defined it in America in the late 1950’s, has become more prevalent in India now as a proxy for object based art. And as was the case with European and American performance in the 1950’s, into the 1960’s and 1970’s, that sought to challenge and open up art and aesthetics to a wider audience; a new generation of artists, ‘Sahej Rahal’ (Mumbai), ‘Sonia Khurana’ (New Delhi), ‘Tehaj Shah’ (Mumbai) , ‘Monali Meher’ (Mumbai), ‘Kiran Subbaiah’, (Mumbai), ‘Manmeet and Shantanu Lodh’, (New Delhi), among them, are in India all employing more performative strategies for their wish for a greater enterprise for the arts, as they diverse and facilitate projects that are intentionally without due diligence to the conventions of a closed gallery space, and to the notion of an otherwise more object based experience.

Theirs is an investigation into the elemental preoccupations of our lives, through social and cultural exchanges as performance and project based works; that actually have the audience feeling a heightened sense of everything the artist is feeling; as the work is firmly in and of the moment. And the democratising of art through performance and these kinds of interventions as such, in their loosest sense, comes about in knowing that an audience’s potential experience of such works is already within their grasp. As the principle forces, materials and sensations, are born of a shared reality.

And it is as a consequence of a more multi-disciplinary approach employed by artists in India now, which I have argued has come about as a consequence of a widening of aesthetic interests and influences, and also in part due to the commodification of art by European and American markets, that has encouraged Indian artists to think more laterally about their own practices. Employing theatre, film, photography, fashion, design, and dance to engage in ideas and project based works that are on-going, even possibly without end. And at the heart of a more didactic debate, where artists employ such diverse mediums and approaches, that the audiences are having to invest themselves in the works.

As instead of the routine of buying into high art, with a painting or accomplished sculpture, which suffices for the majority of ‘cultured’ people; performance, theatre, film and dance, indulge in sometime much more messy and positively democratic, that as Nikhil Chopra describes, ‘are to do with the highs and lows’ of life.

For Chopra then European and America performance art were a huge influence upon his own practice, mentioning the Americans ‘Cindy Sherman’ and ‘Eleanor Antin’, and the Serbian, American ‘Marina Abramović’. And when pressed Chopra fondly recalls visiting Eleanor Antin at her New York studio, Antin has since died, but she was ‘someone who heavily influenced (his) work’. And tellingly for Chopra, ‘she asked why I wasn’t pushing particular ideas much further’.

The significance of what Chopra was wanting to become a part of, and the influences that were available, came much later to him, as he openly divulges something of the frustration of wanting to be able to express himself but not being entirely aware of what is was he wanted to do exactly.

Whilst referencing the leading performative protagonists of the modern period, Chopra explains something of the lack of exposure in India to a more didactic art history that wontedly encouraged greater levels of experimentation. Such stifled circumstances I suggest are to do with schooling, and the academic and intellectual infrastructures available in India to emerging artists, within a relatively immature art scene. Chopra ponders my principled tone, agrees and subsequently admits to a lack of confidence initially, ‘I wasn’t exposed enough to art history, I considered I was lagging behind, and I was very conscious of my own immaturity in terms of criticality, I didn’t have a gutsy spirit initially and it’s about confidence, as a painter, sculptor, the artist carries the burden of art history, a blank canvas can be utterly daunting. Performing alone, opening a blank document is a leap of faith; it is about putting yourself out there.’ And for Chopra the exposure and vulnerability he initially subjected himself to, was a necessary evil, in order he develops as a human being and artist. ‘Performance is another medium in which I am allowing myself to be as successful as I am allowing for the possibility for failure. Failure really is built into the performance and there is of course a sense of exhibitionism about what I do.’

Chopra’s beguiling honesty facilitates much of our conversation, and in such moments of candour the accomplished performance artist inadvertently touches on the vast parameters of his work, and poignantly addresses the notion that failure is as significant to his performative practice as are the rewards of success. And such a turn of phrase ignites your imagination, as you bear witness to the impossible fragility of each of his choreographed compositions in person and replay them in your mind. A situation in which you can see a man effortlessly move between performative silence, solitude and the final salvation of his charactered incarnation; as he positively affirms one’s belief in life itself.

Since his residency and associated performance at KHOJ in 2007, Chopra has developed an incredibly sophisticated programme of performances that have in the past five years stretched the entire world. And he manages to address such relevant issues, as ‘personal and collective cultural history’, ‘the question of identity’, ‘the role of autobiography’, and the ‘politics of posing and self-portraiture’, as he puts it, with such gifted intelligence, that he has successfully moved the debates so much further forward.

Working at the cusp of theatre, performance art, drawing and installation, in the last three years Nikhil Chopra has done a series of leading choreographed actions, that have included a window performance in Berlin in October 2011, in which he was dressed in a black paper costume as an exhausted construction worker covered in a blackened layer of soot; for which he performed for five hours. In November 2011 at the Zacheta National Gallery, Warsaw, Chopra ascended and descended the substantial gallery staircase whilst being covered in paper, molten chocolate and cream. In November of the same year, Chopra performed a show called Liberalis, which he interpreted as ‘the freedom of expression’. For which he dresses in a stiff paper military style uniform that falls apart during the performance to reveal vivid pink underwear. In March 2012 Chopra stood naked for five hours at the GlogouAIR space in Berlin, during which time he feverishly drew in charcoal into the leading wall of the gallery whilst blindfold. In April 2012, as a closing performance for his yearlong residency at Grüntaler, Berlin, Chopra addressed the predominantly Turkish neighbourhood by dressing as an Afghan/Asian bearded man who having blackened the room with a roller and brushes, coarsely drew the Istanbul skyline from memory and then endeavoured to whiten himself, his clothes, and beard as a political reprisal. And in April 2012 in association with Galeria Continua, San Gimignano, the artist archived one of his most accomplished performances to date. Lasting for close on 99 hours in total, five days in total, Chopra was inspired by the 15th century Italian artist Benozzo Gozzoli. During the performance Chopra dressed lavishly in bygone Italian costume, with the corresponding charcoal and coloured drawings of the surrounding landscape, produced during the prolonged performance in and outside of the Arco dei Becci exhibition space, being available for display for several months afterwards.

When given to considering such performances, and the scale and sophistication of his work to date, there is an unabashed confidence about Chopra now that might well have shifted his initial uncertainty about himself onto his audiences. As the fear of being scrutinised and the subject of attention is something we would rather avoid at all costs. And his having successfully levelled out his and our vulnerabilities within a given space, that make for such engaging and equally mesmerising performative works.